What Will We Say to Each Other?

from Essays

Remarks at the Fulbright International Students Enrichment Seminar

Washington, D.C.

Wednesday, March 28th, 2012

A few days ago, I returned from a very moving trip to Egypt. One of the privileges I had was the chance to teach some high school and college classes. I talked about the subject of poetry and politics, poetry and protest.

In one class, just so our conversation wasn’t all passionate and serious, I asked some University of Cairo students if there had been any good jokes about the revolution. They had several to share. I think with any subject that’s deadly serious, there’s usually some powerful humor that gets right to the truth.

My favorite joke was the one about the worried Army commander who went to Hosni Mubarak after watching the protests in Tahrir Square. “Mr. President,” he said, “Everything has come to an end. You should write a farewell speech for the people!”

And Mubarak answered, “Oh? Where are they going?”

Where are the people going?

Riffing on Martin Luther King, Jr., President Obama has so eloquently said that the arc of history bends toward freedom. On a planet of seven billion people, of many nations and languages and beliefs, there are many arcs of history, there are many journeys toward freedom.

Sometimes, the curvature of the earth on the horizon looks like a slow, graceful slope. Far away, but we tell ourselves we can get there, we can do this, with calm and gentle change. And sometimes, up close, the arc of history can seem like a confused, dangerous, twisted knot, that’s tangled and barbed, difficult to unravel.

One of the other great moments of humor in Tahrir Square was broadcast around the globe when cameras captured a weary man sitting on the ground, weakly holding up a protest sign. It said in Arabic, “Would you leave already? My hand is hurting.”

In Egypt, people’s hands continue to hurt. People told me their heads hurt with the complexities they face, with the cacophony of voices and competing interests and ideologies. Their hearts hurt with the suffering and the violence that presaged the revolution and that continues after it.

There are no easy answers. Always, behind the slogans, behind the marches, underneath the placards, however weakly held aloft, there are unanswered questions. There is struggle, there is sweat and sometimes blood, and always the arc of the journey toward something uncertain but hoped for.

One of our great Founders, the writer Thomas Paine, understood that exhaustion. He said, “Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom must … undergo the fatigue of supporting it.”

Or as I saw on a sign at Occupy Wall Street in New York, after a few months into the protest, when people started complaining about the encampment – the smells, the noise, the confusion:

“Sorry for the inconvenience,” the sign read, “we are trying to change the world.”

I love the signs and slogans of protest.

Another, that I saw at a Tea Party rally, said, “Generic Angry Slogan!”

And another that I saw on television at the John Stewart and Stephen Colbert protest as parody event here on the Washington Mall read: “We have no idea what we’re talking about!”

Of course, one of the great slogans of American protest is: Question Authority.

In the United States, we think of this coming from Vietnam protests. But it was first written by Benjamin Franklin who said he took it from Socrates. But it’s cropped up in the Tea Party Movement.

Which it turns out is full of Fulbrighters. I’ve recently been reading books by two of them:

Ronald P. Formisano, a University of Kentucky history professor, who went to Italy and wrote a book called The Tea Party: A Brief History.

And Elizabeth Price Foley, a Fulbrighter to Ireland, that great land of protestors and poets where my family is from, wrote a booked called The Tea Party: Three Principles.

One of the arguments Foley makes is that much of what the Tea Party is and does and stands for has been horribly distorted by the media. It’s interesting because, I have to admit, when I was Googling images of Tea Party and Occupy protests to look at their banners and signs, over and over again, the focus was on the cool, hip and clever signs at Occupy gatherings and the misspelled or factually inaccurate signs that reporters found at Tea Party protests.

It makes you wonder. It makes you question authority—the authority of journalists and the Establishment, which includes my own friends.

A Fulbrighter from Egypt reminded me, of course, that the slick, the fashionable and the most literate have no special access to the truth. She said the most powerful sign she saw at a protest was a farmer who had come from the Nile delta to the center of Cairo carrying a sack of vegetables on his back. He could not read or write. But he said, “I carry my protest on my back. The work for which I am not paid a fair price.”

Fulbrighters have observed and participated in protests everywhere. From Tiananmen Square to Tahrir Square to perhaps even some protests at these round tables before the night is out.

You are gathered here in Washington this weekend studying activism and protest and how they have shaped American politics. I understand that you’ll actually be having a mock Presidential election. And when I heard that, I have to admit, I was a little disappointed to see where I was seated. All your tables say “Democrats” or “Republicans” or “Independents.”

But my table? Somehow, I don’t think this is an image that’s going viral and getting people excited: a guy in a suit under a sign that says, “Reserved.”

But the man in the suit who founded this program back in 1947, Senator J. William Fulbright, did not want Fulbrighters to be reserved. He said, “In a democracy, dissent is an act of faith. Like medicine, the test of its value is not its taste, but its effect.” And he said, “The citizen who criticizes his country is paying it an implied tribute.”

I’ve been talking about signs and slogans—and they’re easy to mention in a speech—but that’s not really where true dissent lies. It’s not what true protest or where change happens.

You could see this in the example of another Fulbrighter, a young performance artist from Greece, named Georgia. Because she believed no one should stand out or above anyone else, she only uses her first name.

Georgia was in New York in the very first days of Occupy Wall Street. She had taken part in many protests in her own country as Greece was being convulsed by economic shock and hardship.

And what she found in Manhattan was the familiar American-style protest: the kinds of banners and signs I’ve been talking about, the lists of demands and speaker after speaker yelling commands and slogans into the megaphone.

She said, but this an effective way to protest. She grabbed the microphone and told the crowd, “You’re not here to shout or even just speak at people. You’re here to have a conversation.”

Protest as conversation. It’s been a strange, often frustrating, sometimes easy to mock, but essential ethos of the Occupy movement. And if you think about it, true conversation is democracy. All sides get to speak. It continues to be such a radical idea.

And true conversation, the one that brings unheard voices to the table, emerges not from agreement, but from dissonance—when we don’t agree, when we’ve talked but haven’t listened, when we’ve stood by and haven’t stood up.

The poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox said that to stand by when we should protest is “to sin by silence.”

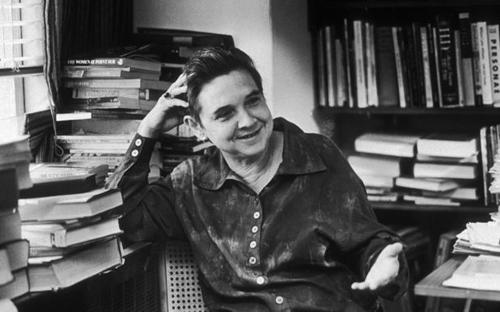

A few hours ago, the great American poet, Adrienne Rich died. There is so much I’d like to tell you about her. But dinner is coming.

But I want to leave you by giving a short tribute to this extraordinary artist. It is fitting that we do so here where we’re talking about protest and activism. And it is fitting to do so during Women’s History Month. Adrienne Rich was a brilliant, fearless writer—a feminist, an activist, someone who truly spoke truth to power.

In keeping with Wheeler Wilcox’s argument that we sin by silence, Rich wrote, “Yes, lying is done with words, but also with silence…. Telling the truth creates the possibility for more truth to be told around you.”

I’d like to think that this gathering of Fulbrighters is evidence of your willingness to listen and study and find out what the truth is and to take the risk of trying to tell it, to take the risk of making room for more truth to be told around you.

In our culture of bravado and aggression, Rich wrote something about dignity and protest that a friend quoted to me a long time ago. “There must be those among whom we can sit down and weep and still be counted as warriors.”

Perhaps, if you know the work and life of Adrienne Rich, you will weep with me for this eloquent, fallen warrior.

And if you have not read her, I urge you to, even this weekend as you think about what true protest means. Protest can be in our tears and our conversations as much as our signs and slogans.

Let me leave you with just a few lines of one of her great poems:

and I ask myself and you, which of our visions will claim us

which will we claim

how will we go on living

how will we touch, what will we know

what will we say to each other.

What will we say to each other? The question is urgent. Never stop asking it.

Thank you.