Troubling the Water

from Essays

Remarks for the Fulbright Awards in Distinguished Teaching Program

Fulbright Teachers Exchange

Washington, DC

April 4, 2013

Troubling the water.

An old Jesuit teacher of mine shared that expression with me when I was in high school. He told me that’s what teachers do.

The expression comes from Chapter 5 in the Book of John. John sets the scene in Bethesda, not our Washington suburb where Bloomingdale’s is, but a pool of water near the sheep’s gate in early Jerusalem, where sick people went to be cured. Interestingly, “Bethesda” means two contradictory things. In Hebrew and Aramaic, it means both “house of mercy” or “house of grace. But it could also be a pun meaning “house of shame or disgrace.”

I don’t want to affect local property values, but I want you to hold that contradiction in mind—shame and grace—while I quote from King James version of the story:

“For an Angel went downe at a certaine season into the poole, and troubled the water: whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in, was made whole of whatsoever disease he had.”

So sickness turned into health, ignorance into strength, a house of personal fear and shame turned into a house of possibility and grace—all because an angel troubled the stagnant waters, stirred fresh air into what was flat and still.

Troubling the waters. That’s how my teacher taught me to understand teaching. And it’s stuck with me.

Before you worry that I’m going to start giving a sermon, though, I just want to explain that what you do, what all teachers do, is so important, so urgent that it’s hard for me not to talk about it in dramatic and emotional terms.

At a time when we are worn-down by the demonization of teachers, by jargon that attempts to measure education like factory widgets, I hope you’ll indulge me a few hallelujahs, a little old-fashioned praise of the teaching profession.

I believe by troubling stagnant waters, you do something close to miraculous—providing cures to things that ail us: from the diseases of poverty and troubled homes and lack of hope, you offer knowledge and dignity and opportunity. From the diseases of prejudice, you offer tolerance and understanding. From the dis-ease, the un-ease that comes from being unsure of our future prospects, uncertain of our place in a crowded, complex and rapidly changing world, you offer the tools and the strength for students to create meaningful lives.

John Stuart Mill wrote that teaching is the noblest profession, because, “while physicians only cure one person at a time, teachers instill greatness in many, who themselves go on to do good things.”

And there’s good reason to believe that great philosopher. The idea of nobility actually has its origin in education. It comes from the word gnoscere, which means “to come to know”; not just knowing, but coming to know, which is learning.

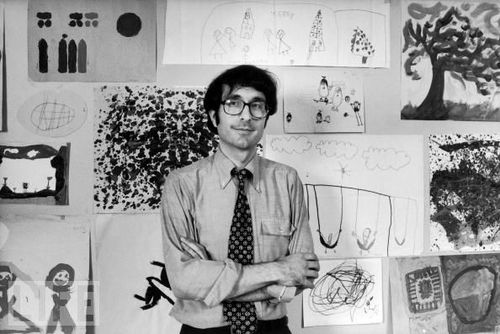

Today I understand you’re going to be working with Veronica Boix-Mansilla from Harvard’s Project Zero. Project Zero was started by the psychologist, theorist and Fulbright scholar, Howard Gardner.

Gardner created the well-known theory of multiple intelligences, which explains how people learn things in different ways, how we come to know things in so many different ways—so many ways for children discover their innate nobility, you might say—and so there isn’t just one way to measure this intelligence. Which also means there is far from one method, one curriculum, one strategy to teach.

Gardner wrote a book with another great psychologist—and Fulbright scholar—Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who created the popular idea of “Flow,” which is the sense of attention and engagement in work that makes people happy and productive by putting themselves in new experiences, creating a balance between new challenges and skills we already have—stretching ourselves to our limits.

We know the idea by many names: flow, being in the zone, in the groove—doing something that requires such intense concentration, everything else falls away.

And when that happens, Csikszentmihalyi says we experience a kind of ecstasy—literally standing outside ourselves—participating in a reality that is so different from everyday life.

Gardner and Csikszentmihalyi collaborated on a project to blend their two areas of research to explore how the ways we learn, the ways our curiosity is piqued and we develop passion for our goals in life. They wrote a book together called Good Work where they argue that, “if the fundamentals of good work—excellence and ethics—are in harmony, we lead personally fulfilling and socially rewarded lives.”

And I would say to you that teaching is exactly that kind of good work. Gardner said once at a lecture I attended, “I want my children to understand the world, but not just because the world is fascinating and the human mind is curious. I want them to understand it so that they will be positioned to make it a better place.”

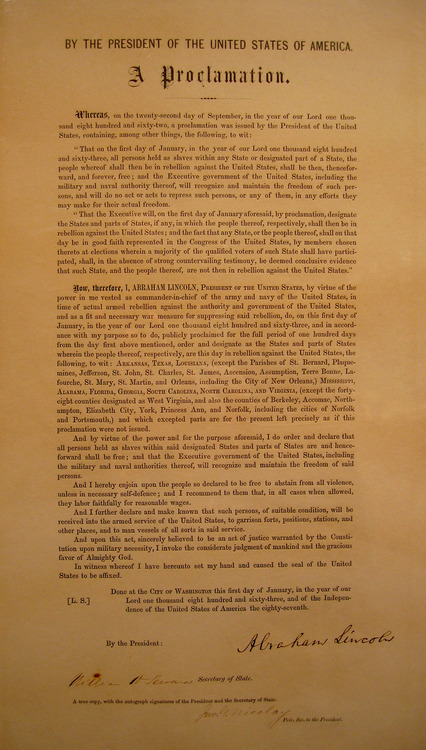

Making the world a better place. Teachers help us do that, teach us to want to do that. If I can bring back the hallelujiah chorus for a moment and steal a phrase from Abraham Lincoln, I would say that teachers are “the better angels of our nature.”

You know, speaking of President Lincoln, this year marks the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, which paved the way for the Thirteenth Amendment. You’ve seen the movie and you know about the political machinations to get that historic amendment through Congress.

Emancipation. It’s a weighty word, but it literally means to take ourselves out of the hands of others. But then what? You know that emancipation has meant a long history of struggle for freedom that still goes on.

Frederick Douglass said it best: “Education … means emancipation.”

Teachers set us free.

And that’s exactly why we always remember our best teachers because they were the ones who set our minds free, let us see some part of the world that had once been invisible to us, just beyond some horizon.

I remember my first great teacher: she was my fifth grade music teacher. I grew up in a very small farming community and had never left my town before until she took us to sing in the county youth choir. Our little group expanded from ten small voices to one hundred and fifty.

So many kids I’d never met before. So many voices. I was astonished. And I believe Marisol Ponte-Greenberg, a choir teacher who taught traditional music in Argentina, knows a lot about that astonishment.

But okay, enough of the choirs and the angels. I have certainly never been called an angel!

But like you, I am a teacher. And I know that good teaching is really not a gift from the heavens. In the end, it really comes down to hard work. And today is a celebration of that hard work. The hard work you actually do:

Whether it’s supporting Mexico’s LGBT youth in its public schools as Ileana Jimenez did or helping Moroccan students learn by using their mother tongue of Darija as Farah Assiraj did or teaching Singaporean students that their environment can be used to clean itself up through phyto-remedition as Eric Goff of West Virginia did.

The hard work of leaving home to go somewhere else, to Finland, South Africa, Argentina, the UK, India, Mexico, Morocco, and Singapore, and to learn and to educate.

You’re here today because, as some of the best teachers in our country, you’ve undertaken the hard work of crossing borders, borders so often defined by bodies of water—rivers, lakes, and oceans—the real and imaginary waters you troubled.

But in crossing those borders, in creating these powerful teacher exchanges, you have actually changed the map of education. It’s no longer rigidly here or there, us or them, my students and their students.

And that, above all else, is the genius of Fulbright. For the past sixty-five years, this program has been a large scale, complex system of making new maps of the imagination, new worlds of exploration and connection—or as the work of Distinguished Fulbright Teacher Lilliana Monk explores—new human geographies of friendship, collaboration and understanding.

In a world in which most people—even in the 21st century—will never live outside the country they are born in, all of you have helped find new ways to unite us.

Whether it’s looking a group performance in mathematics classrooms in Finland, learning about biodiversity in South Africa, or learning to develop communication skills through art and technology in Argentina, you have all been making new maps of what we know, who we know, and how we know.

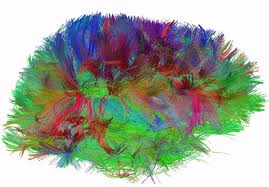

One of my favorite Fulbright mapmakers is Dr. Henry Markram, a Fulbright alumnus from South Africa. He’s been in the news a lot recently for his Human Brain Project, which is a large-scale digital mapping of the brain.

Dr. Markram is turning four vending-machine sized black boxes in a basement at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology into a virtual networked equivalent of the human brain.

This is a map of unprecedented scale. As Jessica Pritzker knows from her Fulbright teacher exchange work on neuroscience, the brain has nearly 100 billion neurons. That’s a total of 100 trillion connections. Dr. Markram’s has enlisted 150 institutions around the world to help with the mapping, that’s how massive the project is.

And now, own country is getting involved. Just this week, President Obama announced a dramatic initiative to map the human brain.

It’s important work. It’s exciting work. It may even be unsettling work. What will be revealed to us about the nature and mechanics of how we think, how we learn?

One thing I do know, is that this kind of quantitative scientific knowledge will never replace the emotional, personal, creative and practical intelligence that are at the heart of teaching- the map-making that helps point us to the future as prepared as we can be and as thrilled as we should be.

It’s hard to find the right words for what teaching is. Beware of anyone who reduces it to test scores or evaluations or even algorithms and neural maps.

I’ve looked to metaphors—to water, that gets wonderfully troubled, to the natural boundaries, often formed by water, we have needed to cross, to maps that help us find our way, and, yes, to angels hovering over it all, just to remind us that there will always be something mysterious, something otherworldly about the skills that teach us to comprehend, protect, treasure and live peacefully in this world.

It’s the wonderful and urgent mystery of what you do that we’re here to honor today. And it’s a privilege to say thank you.