The Shipwreck of Pandora: Finding Hope in Science

from Essays

Remarks to the Fulbright Science and Technology Fellows

Tuesday, June 11, 2013

Washington, DC

Strange things sometimes happen over lunch.

Take this very day, June 11th. Not here in the humid Washington basin, but off the coast of the Land of Oz. Onboard a ship on a flat, calm southern ocean under horizon-wide blue skies pierced only occasionally by perfectly-round white cloud—and nothing else as far as you could see.

The June 11th I’m talking about was in 1770. And by Oz, as you probably know, I mean Australia. 243 years ago. It was a warm, but crisp day, the start of winter in the southern hemisphere.

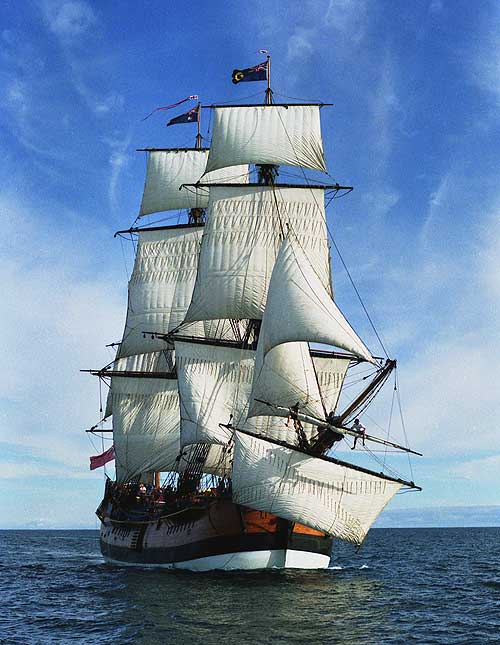

And it was lunchtime for Captain—actually, he was still only Lieutenant—James Cook on his famous ship, The Endeavor. Cook was on the first of his three great voyages of discovery, in search of what at the time he only knew to be some fabled “southern continent” that no European had yet seen.

From Cook’s journals we read

We dined today upon the stingray and his tripe: the fish was not quite so good as skate … the tripe everybody thought excellent. We had it with a dish of the leaves of tetragonal cornuta, boiled, which eats as well as spinach or very near it.

Don’t you just love the British?

Unfortunately, though, Captain Cook’s midday meal was rudely interrupted. His ship lurched forward and suddenly stalled mid-ocean. The wooden planks creaked, the crew started shouting. The Endeavor had hit something, but land was nowhere in sight.

During his quiet, delicious and healthy lunch, James Cook stumbled upon, bumped into and accidentally discovered the largest structure of living organisms in the world: the Great Barrier Reef.

The botanist onboard, Joseph Banks, was not particularly amused or enthusiastic:

The dreadful time now approached and the anxiety in everybody’s countenance was visible enough: ear of death now stared us in the face; hopes we had none but of being able to keep the ship afloat till we could run her ashore

But free her the sailors did, with the help of the onboard astronomer and a small retinue of scientific assistants and artists. After a hair-raising escape, 11 days later, on June 22nd, the Endeavor steered into a gorgeous bay, then silently up the mouth of a river. Cook’s next great discovery: the north coast of the great continent he had been looking for. Here was Oz, the great Down Under, a land, of course, that Cook immediately annexed for the Crown, saying it was terra nullius, no one’s land. Big surprise: he named the river Endeavour and the beach settlement Cooktown. And I’m sure you can imagine one of his first meals: kangaroo, of course.

But back to today, that day of the interrupted lunch, the surprise, anxiety, and unexpected discovery. It took Cook and his men all day and more to free his ship. So, at first they weren’t at all interested in what they found. They wanted to flee, to go where they were looking to go.

But by finding the Great Barrier Reef, Cook found something all of us would become fascinated with for forever: one of the seven wonders of the natural world, a great, living, teeming body of undersea life—from forests of anemones to leatherback and flatback turtles to dwarf whales and humpback whales and humpback dolphins, nine species of seahorses, four hundred species of coral and more than five hundred species of algae and seaweed. He found a vast array of extraordinary flora and fauna living as a giant organism, an orchestra of life in harmony.

One of the most beautiful places to see the Great Barrier Reef is evidently from outer space, which, given the damage done to Endeavor, Captain Cook might have preferred.

But Cook’s spectacular lunch spot is in growing jeopardy. Here’s how to put things in perspective: the first large reefs in the area began more than half a million years ago. The current living coral reef is itself at least 20,000 years old. And more than half of it has died in just the last 25 years.

Enough to make you put down your fork.

I began writing this speech with some excitement about Captain Cook’s spirit, an ethos of ambition that seems to be at the heart of scientific inquiry: the willingness to take the kind of long-shot risk—of approaching the cutting edge, of nearly sailing to the ends of the earth—that Cook took in order to reach discovery. It takes a passion I think all of you know about and have.

And I still have that sense of thrill when I read about your own research and study, your own ambitions for discovery. But my optimism and, I’m sure yours too, is blunted by the knowledge of the consequences of human ambition. It is climate change, pollution, even damage from shipping and more than 1,500 shipwrecks that have endangered the Great Barrier Reef and countless other ecological systems in the world, at rates compounding startlingly in just our lifetimes.

I love the names of ships, their histories. Endeavor is a wonderful name for an explorer’s ship because in comes from the Latin expression “in dever” which means “in duty,” which comes from the word for debt. An endeavor is something you owe, which later came to mean “the pains taken to achieve something.”

You’ve been experiencing the joys and pains of the immense focus discipline to prepare for your doctorates. You’ve been doing something that you owe to your families, your teachers, your countries, to this program.

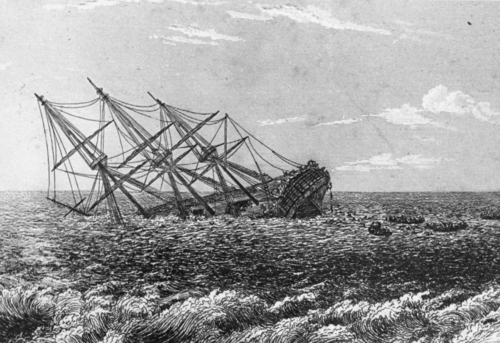

But let me leave you with another ship, one that foundered on the Great Barrier Reef only 20 years after Endeavor’s close call. That ship was Pandora. She had fought against the Americans in the Revolutionary War, and on this fated voyage she plied the South Seas in search of the mutinous crew of The Bounty. Pandora found 14 of Bounty’s crew in Tahiti, including the ship’s fiddler. But Pandora’s captain wasn’t a music lover. He locked his fourteen prisoners in in a makeshift cell, just eleven-by-eighteen feet, built on the quarterdeck, and called, of course, Pandora’s box.

And then on the late afternoon of August 29th,1791 – long after lunchtime—Pandora struck the Great Barrier Reef. She sank the next morning. Pandora’s box broke open: 31 crew died and 4 of the 14 prisoners.

Pandora means “all-gifted” or “the gift of all.” Hesiod tells us in Works and Days that Pandora was the first woman on earth, forged of water and dirt by Hephaestus, the god of craftsmanship. And all the gods gave her presents: Poseidon gave her pearls and the promise she would never drown. (He obviously wasn’t listening when the English shipbuilders hoped their ship with that name wouldn’t sink.) Aphrodite gave her beauty, Athena gave her style and grace, Demeter gave her a green thumb, Apollo taught her music, Hermes gave her speech and cunning, Hera gave her curiosity.

So the all-gifted Pandora was blessed and privileged, like those of us here. But, of course, you know she was also born cursed. It was inevitable she would squander her gifts because of that last essential but dangerous gift from Hera: curiosity. Pandora just had to see what was in the box – and all the ghosts of pain, struggle and misery rushed out into the world: disease and death, greed and dishonesty, hunger and need. From then on, all other humans would have to toil, work and suffer.

Now have I gotten everyone in a joyful mood in time for dessert? Shipwrecks, environmental disaster, squandered gifts and suffering. And add to that the news that, because of budget cuts, this is the last class of the extraordinary program of Fulbright Science and Technology Fellows to fund a small group of the very best young scientists to get their PhD’s in the United States.

None of you is a stranger to hardship. Even at your young age, each of you has faced failure and loss. But the thing we can’t forget is what remained at the bottom of Pandora’s box after all the evil escaped.

There was a slight, meek girl curled up and hiding there, holding a sprig of half-wilted flowers. Hesiod says her name was Elpis. The Romans called her Spes. The Greeks were ambivalent about her; the Romans built her lavish temples. In both languages, her name means hope.

You leave here with many gifts—some of them possibly double-edged and dangerous—but the gift I ask you to keep safe and always within you is that small, shy spirit clutching the partly wilted flowers. Because in the end, hope is most necessary, hope makes the most profound sense, when trouble is in the air, in our worry and in the doubts we harbor; hope is what we have taken great pains to achieve.

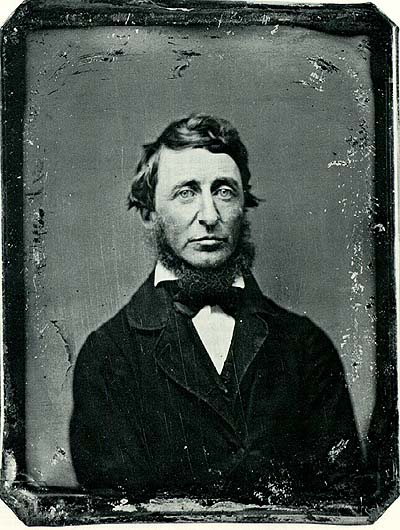

I’ve gone far afield to the Oz and lands of mythological creatures, so let me come home—to a writer and thinker as American in his philosophy of pragmatism as you can get, Henry David Thoreau, a man who lived on a famous pond but never left the solid earth of his native New England.

Thinking about the way we shape our hopes, endeavors, and ambitions, Thoreau wrote, “Do not be too moral. You may cheat yourself out of much life so. Aim above morality. Be not simply good, be good for something.” This is the pragmatist’s answer to finding hope cowering in the bottom of Pandora’s box.

How do you take your talents, your research, your skills and put them to use? That seems to be the moral dimension of science: to share with others in order to make the world a more connected, and possibly better, place.

Fulbright—and your work—are about the collaborative spirit of exchange: of ideas, experiences, knowledge, and passion.

Share that knowledge, stay connected to Fulbright and to one another. Remember that what you do and who you are must not only be good, but good for something.