Stories in the Wilderness and in the City

from Essays

Remarks to U.S. Fulbright students and scholars departing for North Africa and the Mideast

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Key Bridge Marriott

Arlington, Virginia

When I walked home a few hours ago to write something to share with you tonight, I couldn’t help thinking about another night when the weather was just as beautiful—the kind of weather that gives you heartache it’s so lovely.

The night I was thinking of was just a few months ago. I was in Rabat in a place called Chellah in the hills on the outskirts of the city, overlooking the Bou Regreg River, which opens out into the Atlantic Ocean in the distance.

Chellah is the site of an ancient Roman port town called Sala Colonia, founded in about the year 40. The Romans abandoned the city less than 100 years later and then, sometime in the 14th century, a Moroccan sultan built on top of it. He built a mosque and huge minaret, a school and royal tombs.

Now it’s a public garden with this strange and wonderful mix of Roman and Moroccan, classical and medieval, solitary columns and overgrown arches, orange and olive trees, Arab mosaics and Latin inscriptions, the smell of lavender and a sea breeze.

But what you actually notice first about Chellah are its inhabitants. Hundreds of cats wander the paths and lie in the shade. And then there’s the air force: huge storks perched in gigantic nests of sticks and branches they weave together on the top of the minaret and telephone poles and the Roman columns.

It’s a site Dr. Seuss or Tim Burton or the writers of “One Thousand and One Nights” might conjure up. It’s definitely a place for storytelling.

I mention it because I need to tell you a sad story of that beautiful spring evening in Rabat. I was in Morroco with a group of Fulbrighters who were all studying and working and teaching in countries throughout North Africa and the Mideast. A group much like all of you.

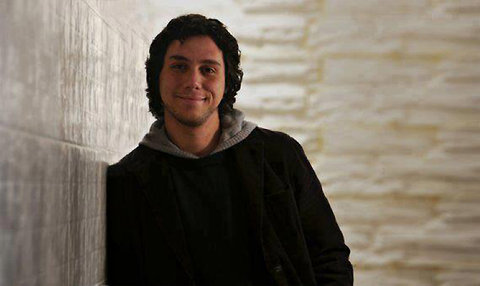

And I’ll never forget walking down the 2000 year old decumanus maximus, which is always the main east-west road in any ancient Roman city, because I was listening to a brilliant, funny and charismatic young Fulbrighter who was telling me about her research on the struggle for women to enter the political process in Bahrain.

Her name was Kelly Dalla Tezza. Two days later, Kelly died in a car accident. She was a remarkable person.

As was Bassel Al Shahade, a Syrian Fulbrighter who studied at Syracuse University. He also died this spring, in the struggle against the dictatorship in Syria.

I’d like to ask you to join me in a moment of silence to remember and honor Kelly and Bassel.

I don’t tell you about Kelly and Bassel to darken this occasion of celebration and thrill as you prepare to depart for what will be remarkable journeys, joyful stories, experiences that I hope you will carry far into old age.

I only tell you about them as a request: I want you to undertake your Fulbright with the same passion, intellect, personal warmth, modesty and curiosity that Kelly and Bassel had.

It is the same spirit the young novelist Ana Menendez had on her Fulbright to Egypt in the fall of 2008. Ana was there when President Obama was elected and she tells wonderful stories of the surprise and excitement people throughout the Mideast had to that election. You will all certainly have stories to tell of reactions to these elections: both the American and Egyptian elections—and the wave of change throughout this Arab summer and fall.

Ana Menendez sent me a note on Facebook just today to share with you. She wrote that with Fulbright,

“I don’t like to talk about ‘making a difference’ because it’s such a cliché and so paternalistic. But what I feel I did do was offer a complication to people’s somewhat simplistic view of what America is. (That I was a woman, with a Hispanic surname who also looked like them further complicated matters!)

And in return they did the same for me.

I always think of Camus when I travel. When you keep the individual in mind, it is very hard to fall sway to prejudice and abstract ideology.”

Keeping the individual in mind. That is why I am dwelling on the idea of telling stories—the sad and the joyful—the importance in keeping, sharing and telling your stories, your encounters with people.

The great American poet Muriel Rukeyser once wrote, “The universe is made of stories, not atoms.”

When I once shared that quote with a writer in Dubai, he said to me, “It’s funny, a few years ago, a sixteen year old girl in Beirut said to me “I am made of stories, not atoms.”

The universe, each one of us. We are our stories.

The writer in Dubai participated in an organization called Haykaya, that is trying to revive the art of storytelling throughout the Arab world.

Long before “One Thousand and One Nights” was composed in the ninth century, skilled storytellers made their living gathering people to hear them in courtyards of small medinas or in grand public squares like Djemaa el-Fna in Marrakech.

The organization Hayaka believes that stories are “the reading of life,” not simply the reading of texts. Their fifth annual festival will take place in Amman in September. For those of you lucky enough to be nearby, I encourage you to look it up.

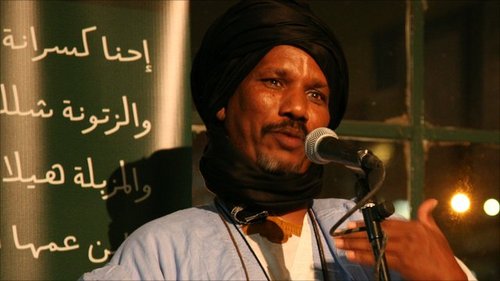

Yahya Rajel, a storyteller from Mauritania who has participated in Hayaka, has said with melancholy that he is afraid storytelling is being lost in modern life. He has said of the traditions from the Mauritanian desert, that “The wilderness is the ideal environment for a story, but people have no time for that now in the city.”

But whether you are an artist or an architect or a nano-scientist or a climate change researcher, you know that is not true.

Stories are made, stories are told every day, in the wilderness and in the city. Sometimes, they are just told differently. Sometimes—in our time—stories are made new.

I’ve been reading a story by a Brooklyn writer, EA Marciano who uses Twitter, Tumblr, Blogspot, and YouTube. And I don’t mean he just writes about them. He actually employs all of these platforms in telling the story.

Mariano’s different characters—with their different styles of speech and visual expression and plotlines—are developed in different social media.

As he’s said, “Twitter is rapid, spontaneous, and fragmented”; Tumblr is for thinking in pictures; and “Blogspot is for raw, aggressive rants.”

YouTube? Well, he says, “I mean, who isn’t making videos these days? It’s an incredible force that allows for the widest range of weird and awesome.”

“The widest range of weird and awesome.” That seems like a pretty good description of what I hope your Fulbright experience will be.

It’s not necessarily easy to tell good stories, of course. As Ira Glass of “This American Life” has said, “Great stories happen to those who can tell them.”

But you’re going to be at a huge advantage by having great material. And we want you to share that experience with us.

I know you’ll be overwhelmed and engaged and busy. As Emily Dickinson, one of America’s greatest conjurers of the weird and the awesome, admitted, “To live is so startling it leaves little time for anything else.” Maybe that’s why she wrote short poems.

But you can do always 140 characters. You can take a picture on your phone. Post to Facebook. Do haiku. Whether you use social media, mail us a postcard, write essays or send us a Powerpoint presentation, we want to hear what you’re doing, what you’ve done.

Whether you use social media or you mail us a postcard, we want to hear what you’re doing, what you’ve done.

Keep in mind what another Fulbrighter, Rachel Smith, told me, “Fulbright is not about changing the world. It is about sharing the world.”

Some economists and social theorists say this is actually a larger phenomenon, that instead of a consumer society we are moving to a “creators economy,” where people are starting to think less about ownership and more about sharing.

Now perhaps these theorists are wearing Panglossian rose-colored glasses. But I do want you to think of sharing as the heart of what Fulbright is.

Whatever your field, whatever your work and research and study, Fulbright is, essentially, a shared world of stories—of the thousands of students and scholars who have come before you, connected to you and all the Fulbrighters who will come after. And connected to all the colleagues and friends and even passing strangers you will meet in the countries where you’ll be living.

All those experiences, voices, pains, frustrations, discoveries, triumph. All those stories …

Fulbrighter Lauren Bohn who was in Egypt in 2011 has written very beautifully about this idea:

“Egypt’s story has at times seemed like an existential struggle between the future and the past.” But, “while photogenic revolutionaries grabbed the world’s attention, the country teems with a varied 80-some million people all their stories.

And all these stories matter, Bohn writes. Because the future is still being fought over, “the voices of different people tell us why ‘revolution’ is relative and why, like in any story, sometimes the most difficult part to conceive is the end.”

So I want to leave you with a request and a challenge. Prove that storytelling is very much alive—in the wilderness and the city, in medinas and souks and villages, among the cats and storks, up in the world’s tallest buildings, out in the slums and labor camps, on artificial islands lined with McMansions, along the fragile coast, in the sandstorms of the desert.

Tell us about the worlds you find and the worlds you make. Tell us your stories. Begin tomorrow or even tonight. You’ve got your whole lifetime to think how they’ll end.