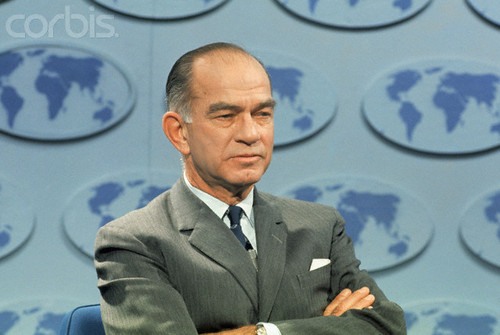

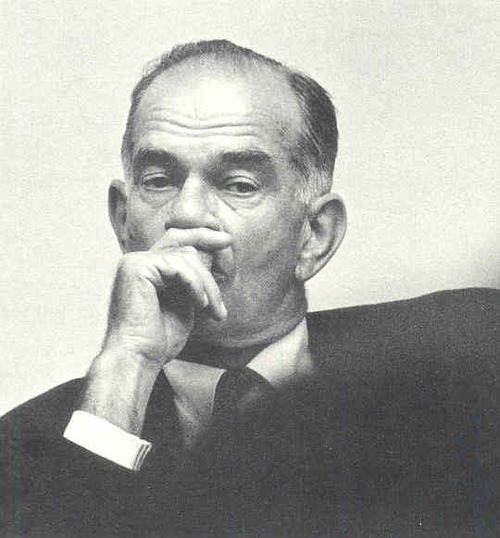

Remembering Senator J. William Fulbright

from Essays

If Senator J. William Fulbright were still with us, he would be turning 108 today.

That’s a lot of candles.

But with a powerful legacy like his–his legislative achievements, his anti-war activism that inspires so many today, and, of course, the world-famous Fulbright Program–he is still with us in spirit.

Senator Fulbright is probably known to most people as the founder of the Fulbright Program, which is the State Department’s leading international exchange program, sending our best students, scholars and professionals in almost every field to study, teach and engage with people around the world in return for the world’s best students, scholars and professionals spending time studying, teaching and living in the United States.

8,000 people participate in the Fulbright Program each year. From 155 countries. And in almost every field of knowledge, from astrophysics to zoology, Arabic to Zulu, arts education to vocational training. Fulbright has been a springboard for Noble Prizewinners and prime ministers, poets and farmers, journalists and engineers. There’s nothing else like it - building tolerance, mutual understanding and shared knowledge, all to create a more peaceful, more connected world.

But Senator Fulbright’s accomplishments in and out of the Senate extend to an even wider range of legislative and moral victories.

He spent his career forcefully inveighing against tendencies to use military force unnecessarily and he was one of the most vocal opponents of the Vietnam War. He was an eloquent skeptic whenever he sensed we Americans were too sure of ourselves, too unquestioning of our beliefs and values, too ready to hit first, ask questions later. He started the Fulbright program by drafting legislation that required the government to sell war surplus supplies and use the money to start the Fulbright Program in 1946. Later, in 1954, he was the only senator to vote against appropriations for the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, the vile home of McCarthyism.

Fulbright came to his skepticism through acknowledging his own terrible moral blindness: he had been a segregationist senator from the South, filibustering against civil rights legislation on several occasions. The racism he learned to rid himself of and denounce was an enduring shame for which he felt he could never be forgiven, though many civil rights leaders did forgive him and called him their friends.

Few legislators have ever been so skilled at the alchemy of turning hate to good, swords into ploughshares. And that alchemical effect extended to those who knew and worked with him. Think of that young part-time staff member from a Place Called Hope who experienced the Fulbright Effect and became an ambitious young governor and President of the United States.

And there’s that young Vietnam veteran invited by Fulbright to testify before the 1971 Congressional hearings on the Vietnam War, who later became a senator and is now the very Secretary of State who oversees the Fulbright program. In fact, Secretary Kerry created the largest Fulbright program in history when relations were restored with Vietnam. And his daughter Vanessa Kerry was a Fulbright scholar.

And, of course, there are the hundreds of thousands of scholars and students on whom J. William Fulbright and his extraordinary program have worked their alchemy to make the world a better place. Wherever I go and meet Fulbright scholars, they always say to me the same four words: “Fulbright changed my life.”

As Senator Fulbright himself said, “The rapprochement of peoples is only possible when differences of culture and outlook are respected and appreciated rather than feared or condemned, when the common bond of human dignity is recognized as the essential bond for a peaceful world.” And that bond is exactly the one that links Fulbright scholars and students to universities, governments, artists, and people around the world, promoting not only acceptance and understanding, but the exchange of ideas, the transcendent values of knowledge and inquiry that link us all, no matter where we live.

Forty-two years ago this month, John Kerry, then a young veteran, testified before Congress on how to end the Vietnam War. After Kerry’s testimony, Senator Fulbright said, “You said you wished to communicate. I can’t imagine anyone communicating more eloquently than you did.”

The eloquence of communication: it comes in many forms. It can be a simple word. “Shalom” or “Shokran.” Or it can be the nuance and complexity of a full year of living abroad in a new language, a new culture. But to use the language Senator Fulbright would have used, it is an ethical duty for all of us as citizens in a interconnected, troubled and complicated global culture to find the eloquence to understand and accept other people, other values, other ways of living.

Senator Fulbright closed that hearing with the young John Kerry by reaffirming the value of our institutions even in a time of acrimony and distrust, when he told the veterans and reporters in the room, “not to be too disillusioned and not to lose faith in the capacity of our institutions to respond to the public welfare.” Secretary Kerry, now the steward of one of those great institutions, said much the same this week after one of the youngest Foreign Service officers in the State Department, Anne Smedinghoff, was killed on her way to deliver textbooks to children in Afghanistan. Anne was only 25. She had been in Afghanistan less than a year. But everyone talks about how fast she moved to engage with Afghanis, particularly women and children. Because of her, the Afghan national women’s soccer team is on its way to getting its own stadium.

Secretary Kerry said, “Anne was met by a cowardly terrorist determined to bring darkness and death to total strangers. These are the challenges that our citizens face, not just in Afghanistan but in many dangerous parts of the world - where a nihilism, an empty approach, is willing to take life rather than give it.”

Anne Smedinghoff lived by giving, trying to make a world of fewer strangers, less hate and more hope. She was a kindred spirit of Senator Fulbright, who said before he died, that he hoped the Fulbright program and other efforts like it would" bring a little more knowledge, a little more reason, and a little more compassion into world affairs and thereby to increase the chance that nations will learn at last to live in peace and friendship.“

In Anne Smegdinghoff’s memory, it’s worth celebrating Sen. Fulbright’s birthday, his passion for peace and the belief he and Anne Smegdinghoff shared–even in the face of conflict and hate-that there is a “common bond of human dignity” and that it’s our responsibility to find that bond, to strengthen it, wherever we are in this troubled, complicated but increasingly interconnected world.