Looking at Your Shoes Instead of My Own

from Essays

Remarks at the Fulbright International Students Enrichment Seminar

St. Louis, Missouri

Thursday, April 12th, 2012

I’m originally a farm boy. But tonight I want to talk to you about cities.

Jerusalem. Belfast. Beirut. Mostar. El Paso. Berlin. Rome. Johannesburg.

Who here has lived in or visited any of those cities?

So you know what it’s like to inhabit a city that has been divided. In many of these places, the divisions were—or are—physical. The walls and barbed wire, the watchtowers, the enforced ghettos, the guns, the rations—these are ordinary facts that millions of people wake up to, the violence of everyday living.

And there are also the divided cities whose barriers were made by laws and tradition, by the barricades of language and the concrete of prejudice that sets hard in the heart.

This very city, St. Louis, in the heart of America, has had those barriers.

(One of the largest race riots occurred in East St. Louis by Jacob Lawrence)

And, yet, it has had a history of remarkable people who have worked to break them down, slip under them, float over them. As the old proverb goes, you show me a mile-high fence and I’ll show you a ladder that’s a mile high and just an inch more.

St. Louis is often referred to in the media as one of the most divided cities in America—divided between city and county, divided racially, economically, divided even in its beginnings, back to when Missouri was first admitted into the Union as a slave state.

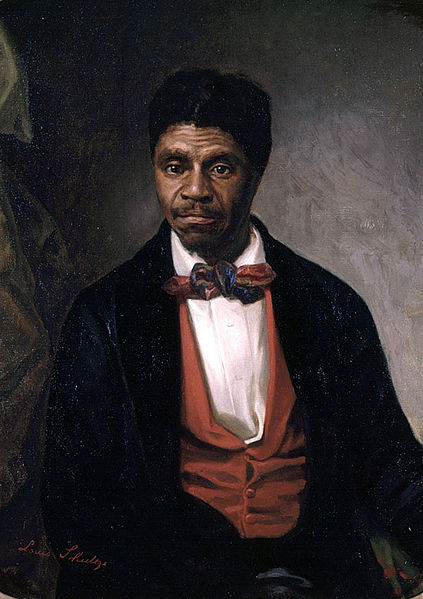

This weekend, you may hear a lot about two people who helped bridge this divide. One is a great American, one of Missouri’s most famous native sons, even though the reason we know him is because Missouri didn’t want to count him as a son. They said he was a slave. Dred Scott.

Dred Scott refused to believe that he was not a son of Missouri. He refused to believe he was not an American citizen. He refused to believe America didn’t believe in itself.

Dred Scott refused. He went to court to voice that refusal. And he changed America. Imagine being a slave in the 1850’s and believing the justice system could work fairly for you. Dred Scott sued his so-called “owner.” Whe he lost and she died, he sued the inheritor of her estate—and the supposed inheritor of Scott himself and his family.

Scott’s case eventually made it all the way to the Supreme Court where, in a ruling tampered with by the newly-elected President James Buchanan, the Court ruled 7-2 against Scott.

The Court said Dred Scott was not a man. They said he was not an American. They said he was property. As Chief Justice Taney wrote: slavery was now forever “beyond politics.” It was a legal fact.

But what’s that saying? Facts can be stupid things. Particularly when they’re wrong.

As the great Frederick Douglass said after the Supreme Court ruled, “The fact is, the more the question has been settled, the more it has needed settling.”

Settled questions often means someone has been silenced. Someone settled on one side and someone settled—shoved, corralled, divided—on the other.

The work of democracy is, in fact, the work of unsettling us. Democracy puts us all together in the honest difficulties of trying to live amidst one another, freely. And democracy is unsettling because it demands that we acknowledge that fundamentally we are all politicians, we are our own legislators. We are what the Athenians, those great experimental democrats, called the polis, the city. And you don’t need to be a New Yorker to know that nothing is settled in the city. The city never sleeps.

Martin Luther King, Jr. so eloquently told us, and President Obama has so eloquently reminded us, the history of the American people isn’t settled. Whether that history comes originally from Addis Ababa or Athens, St. Lucia or St. Louis, American history, American public life is a journey along an arc of progress. And that arc bends toward justice.

The arc is long, but because it’s unbroken, Dred Scott was not silenced. His voice reaches across time, answered by a chorus of other voices that praise and honor and agree with him. Dred Scott’s unsettled, unsettling voice becomes a common voice, a voice that in all its registers speaks hope.

That’s what the Fulbright is about, what the United States in partnership with all our global neighbors is about: a common voice, an unsettled voice. From our divided cities, a shared city, a shared belief.

All of you here came from around the world to be here, to study, to learn alongside women and men of countries and creeds and histories different from your own. It’s wonderful, but, strangely, still uncommon.

Now, I was sitting at my kitchen table while I was writing about the voices and stories and divisions and shared beliefs along this arc of history. And I was thinking about coming here - to St. Louis and the great Gateway Arch. And I started thinking how much would I have to twist things to get from “arc” to “arch”? From Dred Scott to Eero Saarinen. From St. Louis to Helsinki and back – and how would I do that before the keynote speaker got impatient and jumped up to grab the mic?

And I realized—I was actually sitting at a Saarinen table!

Of course, it’s moments like this when I realize it’s a very good thing they don’t actually give poetic licenses because mine would be revoked.

But I promise you, there I was sitting at my Saarinen table having cereal. I’ll post a picture to prove it—and I realized there’s only one obvious way to get from arc to arch. And it’s the reason we’re here. It’s Fulbright.

Sen. Fulbright started this extraordinary experiment because he wanted to bridge divides. This former segregationist senator from Arkansas—who was, in fact, born right here in Missouri—found a common voice with Dred Scott, with Martin Luther King and many civil rights leaders. He even found a common voice long ago with a young woman in Little Rock, Arkansas—our current Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham Clinton, who leads and champions the Fulbright Program

Okay, that’s the arc, but the arch? Helsinki? Saarinen? Well, he wasn’t a Fulbrighter himself, but it turns out that an entire generation of Fulbrighters studied under Eero Saarinen.

And when St. Louis and Helsinki, where Saarinen was from, noticed that a relationship had been built between the two cities, the Sam Fox School at Washington University in St. Louis started to bring in more Fulbrighters from Finland to study architecture here—in fact more than 150 architecture students, of which Fulbright scholars make up a large portion, have come to Washington University in the last ten years.

And big numbers going the other way too. As a professor at Washington University said, Helsinki may be thousands of miles away, but you’d think it was next door.

Next door.

You don’t get next door in a divided city. You don’t talk with your neighbor across a wall. You don’t share the journey of politics together when you don’t share even the same side of the street, when you don’t stand toe to toe.

There’s an old joke about the Finns: How do you know if a Finn is outgoing? The answer: he’s looking at your shoes instead of his own.

Healing the divided city is about looking at your neighbor’s shoes, it’s about seeing into your neighbor’s hearts and minds. And in our global community, your neighbor can come from almost anywhere.

I’m happy to be here tonight in St. Louis. Here with friends. Here in the Fulbright neighborhood. I can’t see your shoes. But I can see your eyes.

And I’d like to close with the words of another native son of Missouri. He’s more famous for living in Harlem, but he was actually born a century ago in a little town near here called Joplin. Joplin is a small city now and it has suffered terribly. Just a year ago, tornadoes ravaged through in an hour and killed more than 150 people. Joplin was ripped in half. But even in its quieter times, Joplin was divided, divided by race. And its native son started looking for words that could heal that divide. I’m talking about the great poet Langston Hughes.

I love Langston Hughes because his singular work somehow constructs a common voice. The magic of Hughes’s poetry is that he made it seem as if it could have come from any one of us. It speaks to something deep, that urge to reach out to a strange world an see something familiar—the shoes, the eyes, the heart.

There is a poem by Langston Hughes that had long been considered lost. It’s called “I look at the world.” It was found and only published in the last few years. I think it’s a perfect poem for Fulbright, a perfect poem for tonight:

*I look at my own body*

With eyes no longer blind— And I see that my own hands can make The world that’s in my mind. Then let us hurry, comrades, The road to find.

Thank you!