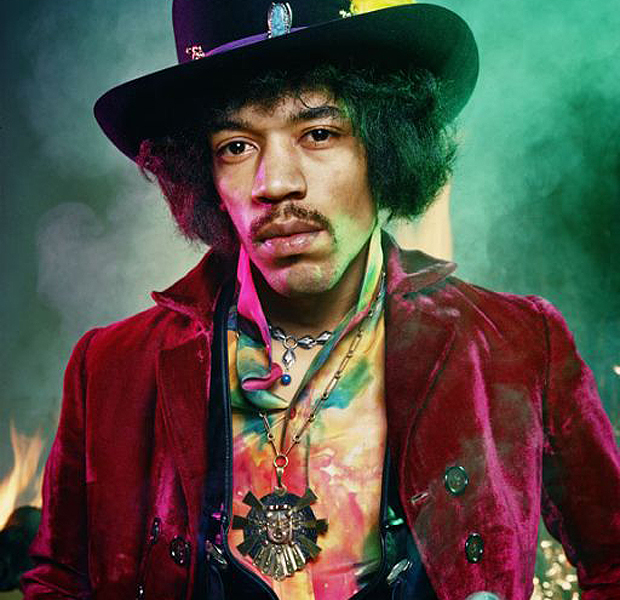

Jimi Hendrix and the Heliopause

from Essays

An Address on Climate Change and Storytelling

To the Fulbright NEXUS Scholars

Washington, DC

September 18, 2013

How about a pop culture quiz for a gathering of scientists and scholars?

I have three quick questions. Three claims about philosophy, profundity and doing good in the world:

Who said: “Knowledge speaks, but wisdom listens.”

Who said: “When the power of love overcomes the love of power the world will know peace.”

Who said: “In order to change the world, you have to get your head together first.”

I’ll make it easy. The answer is the same for all three. They are all the musings of one of the greatest artists of all time.

Jimi Hendrix.

You know, for $11.99 on Amazon you can buy the “Vandor 34010 Jimi Hendrix 24-ounce stainless steel water bottle, multicolored.” It is, the ad says, “Recyclable, Non-toxic and reusable, Eco-friendly and recyclable, with High quality graphic. A Great gift idea.”

I thought really hard about getting one because I was playing “Bold as Love” this morning, remembering that Hendrix died today, September 18th 1970.

I always get a little parched when I’m having my Hendrix Experience. And with “Tears of Rage,” “Smoke on the Water,” “Waterfall,” I thought, “Hendrix water bottle? Why not?” And then, after a little too much online procrastination, I found out that a Hendrix water bottle could actually do some double duty in marking this day. It turns out that September 18th actually is all about water. Today is World Water Monitoring Day.

Happy World Water Monitoring Day. You probably didn’t know, did you?

You have to worry about an environmental effort so clumsily named and marketed. The occasion wasn’t even marked on the organizer’s own website.

World Water Monitoring Day was originally supposed to be October 18th, which is the anniversary of the Clean Water Act. That legislation is one of the signal accomplishments of the environmental movement. Signed in 1972, it was very much a product of Hendrix era and attitude of getting your head together enough to change the world.

But unfortunately, for World Water Monitoring Day, in Canada and in may of the northern European countries that wanted to participate in celebrating the Clean Water Act, October gets just a little too cold. Water is already starting to freeze up north and much more difficult for school children and citizen volunteers to go out and monitor. So they didn’t get a better name and they didn’t market things very well, but they did move the whole thing to the day Jimi Hendrix died. Still, hundreds of thousands of people take part in 66 countries to something very valuable: to study, document and report on how clean and available their local water is.

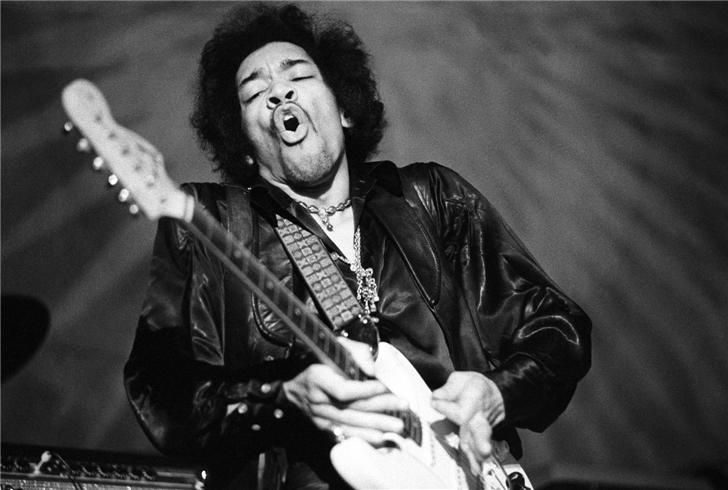

I was thinking about the sources of water, its vulnerabilities and scarcity and it made me think about the lyrics to the last song Jimi Hendrix was known to have played.

It was at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London, two days before Hendrix died. He was accompanying Eric Burdon & War on their cover of Memphis Slim’s famous down-tempo blues classic “Mother Earth,” with its famous chorus:

Don’t care how great you are, don’t care what you’re worth

When it all ends up you got to, go back to mother earth

“Back to Mother Earth.” That’s where Jimi Hendrix went, that’s where the water goes. That’s our home. The home we cherish and despoil, the home we map and measure, the home we’re in danger of making a cemetery for itself.

On a much happier note about Mother Earth, do you know what also happened on September 18th?

In 1977 – perhaps you tell the ‘70’s were my formative years? - Voyager I took the first photograph ever to show the Earth and the Moon together. I remember seeing that photograph in the New York Times. And, you may now have guessed it, yes, today is the birthday of the New York Times, which published its first issue on September 18th, 1851 for a penny a copy.

Last week, you could read in the Times – and in countless other media - the remarkable announcement from NASA that now 36 years and 13 days after it was launched, Voyager 1 has crossed the heliopause and entered interstellar space. No other manmade object has ever done that.

I love the idea of the heliopause: the boundary theorized where the solar winds are no longer strong enough to push back against the winds from other stars.

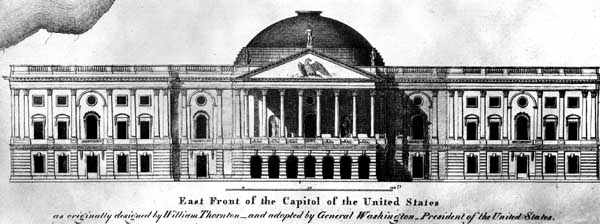

But back again to Mother Earth. Back to the calendar. Back to this city, Washington, DC. It also happens that today, in 1793 – 220 years ago - George Washington laid the cornerstone on the Capitol building across town, where many of you have spent time talking to Congress about climate change, about Mother Earth and her melancholy.

The original Capitol building was brick, clad in sandstone, and later clad in marble as the country got richer. I like to think of the bricks of our polity first coming from the earth as mud and clay, then in George Washington’s hands and now in ours. The urgent fate of the Earth is certainly in our hands. And we need urgent political solutions if we are going to do anything that can make a difference.

This is the fourth time I’ve spoken to the Fulbright Nexus scholars. Once before in Washington, then I followed you to Canada in the snow and then I stalked you in Medellin, Colombia in the spring rain.

I’ve told you stories about the creation of the Giant Brain, Storm Demons, the electrocution of monks, the invention of vodka, even the invention of the word scientist.

And I’ve often used the dates and anniversaries of the occasions we’ve gathered, not because in themselves these coincidences mean something. But because stories and speeches and science all depend on collections of data points to make meaning.

I choose some data, some facts and figures as points of departure because I want us always to think of the work we do, the lives we lead, as connected to the past as much as prelude or preparation for the future.

You have been sharing your research, hypotheses, commitments and passions about how to tell a new climate story, a story that can cut through skepticism, that can break through the paralysis of political will, that can tell about possibilities and hope and not just tragedy and doom. You’ve been explaining specific strategies and technologies for adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change, not only on the precious resources of land, energy and water, but on our mindsets and habits, on our openness to fact, on our imaginations of who we want to be, what kind of world we want future generations to inhabit.

The philosopher and Brazilian politician Roberto Mangabeira Unger has written, “At every level the greatest obstacle to transforming the world is that we lack the clarity and imagination to conceive that it could be different.”

NEXUS, a unique effort throughout the Americas, has been a critical effort in getting Fulbright to have the clarity and imagination to conceive how our own efforts at research, international collaboration and cultural understanding can be different. You have invented a new model.

Jimi Hendrix was once asked if he were an inventor – of wawa, psychedelic music, rock and roll guitar. He always laughed when he heard those questions. He joked that fans and critics often fantasized that he had a “mad scientist approach” to music. But he believed art shouldn’t be reduced to strategies of invention. Instead, he said his music – all transformative art – is “just asking a lot of questions.”

As for those words? “Imagination,” Hendrix said, “is the key to my lyrics. The rest is painted with a little science fiction.”

Now, I am not a scientist, but I firmly believe a little fiction is actually critical to the question of climate change. Not the fiction of false belief and denial, but the fiction of what doesn’t exist now, but that we can imagine, the fiction that could become reality.

To address climate change, we must find ways to mobilize big, collective strategies for regulation, legislation and large-scale investment. That will take immense time, resources and collective will. Right now, that’s science fiction. But it’s a possibility. We have the imagination to make it reality.

We need a radically new narrative, profoundly difference approaches to leadership and the effectiveness of governments and civic organizations. We need to mobilize billions of people and change enough minds to make fundamental shifts in our behavior as consumers and global citizens.

And in the meanwhile, as we work for such a wildly new story, we need to make urgent decisions now as individuals. We can make crucial progress by reducing our own carbon footprints voluntarily, by sharing the kind of monitoring and research, success stories and dead-ends that can quietly add up to a greater movement.

There is fascinating new thinking happening in how this new kind of climate story might become fact, not fantasy.

Whether we talk of Frankenstorms or droughts or other extremes, the threat of climate change, is often presented in narratives of doom.

But Dan Siegel, a noted UCLA psychologist, has done research to show that this might be counterproductive. What he’s discovering is that our cognitive behavior works through maps of neural activity in the brain.

He’s identified what he calls “me” maps and “we” maps of selfish vs.communal thinking and behavior. Dire environmental stories seem to trigger a fight/flight/fear response in us, making us nervous, but trapped and inactive, in a state of denial. But when our stories about the climate appeal to “we-maps” of our families and communities, and ultimately to the world itself, remarkably, our brains respond differently. They trigger us to behave optimistically, to get engaged, to take action.

But how do you tell that kind of story, about positive, action-oriented, public engagement, and tell the truth? Harvard climate scientist Dan Schrag has said that the time scale of making actual change to the climate is staggering. Even if we made the most radical interventions and had the greatest political will, and did everything technologically possible right now to drastically reduce carbon fuel consumption and emissions and change everything we can about industry and transportation, the world would not really see much result for 75-100 years.

How do we think about such sobering realities? How do we motivate people for 100 years from now? How do we ask people to bear costs for which even their grandchildren may experience little direct benefit? What Schrag says to these questions is humbling in its honesty: “I don’t know.”

President Obama’s science advisor has said there are three things we can do about climate change: we can mitigate, we can adapt and we can suffer. We are likely to do all three.

Mitigate, adapt, suffer. Suffering from climate has certainly more than begun. And we have poets, guitarists, and artists who capture our grief. But what about mitigating and adapting?

Here, the stories we must tell become practical again; they don’t need to be science fiction. They must be the kinds of useful stories that come out of our childhoods, that even come out of the motto shared by Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts:

Be prepared.

And this, in fact, is now the President’s focus, his goal for efforts on climate change: national preparedness.

Focusing on preparedness means getting practical, it means translating the complexities of the future into the present, it means making our concerns about the climate local and positive: what can we do now for our families and communities and for people suffering and at greater risk than ourselves?

Not only can being prepared mobilize us to suffer less, it can help teach us more deeply about the long-term nature of the threats to our environment. Regular, constant, visible efforts at preparedness will change how we live, but also who we imagine ourselves to be. And it will change these brick by brick, person by person.

Mitigate, adapt, suffer certainly is not a very optimistic strategy. But I did open with Jim Hendrix’s death, after all. I also opened with water bottles and mass mobilizations to monitor our water. So we can reverse the order: and after being honest about suffering, we can mitigate and adapt. It’s what humans have always done. It is what your work as scientists involves.

Strategies of preparedness–research about how we can mitigate and adapt to climate change, clear truths about the suffering that is likely as the world warms and what we can do about it– embody what the environmental writer Annalee Newitz has called a “grim hope.”

I believe this is the kind of hope we should have. It’s a responsible hope. It’s an engaged hope. But it’s not naïve. It’s not dishonest: the truth as it is, the search for truth as we need it to be, as it might be feasible to imagine the world becoming.

Happy World Water Monitoring Day.