Good Work

from Essays

Remarks at the Institute for International Education

Annual Board meeting

New York, New York

January 28, 2013

I had just come down out of the mountains from a three-week trek in the Himalayas. It was early June, but the weather was so bad, the kind of small planes that had flown us in to the lower mountains couldn’t reach my trekking partners and me.

A white-knuckle trip, but, as you can see, I made it. I took my first shower in weeks and back on terra firma at a more sensible altitude, I had my first cocktail. Who knew you could get a perfect martini at the Dwarikas hotel?

In my freshened state, and in the nick of time, I made it across Kathmandu’s chaotic unpaved streets to a gathering of Nepali Fulbright alumni celebrating the 60 anniversary of the program in their country. There was a long line waiting, hundreds of people who had come to greet the ambassador and me.

From each, a slight bow. Hands pressed in greeting. Namaste. And I smiled and did the same.

At the end of the line there was a small man in his late 8o’s. He slowly walked up to me. But when I bowed, he took my pressed hands in his own and I realized he was holding a frayed and folded piece of paper he wanted me to look at.

I unfolded the paper. It was a letter from 1953 signed by Senator J. William Fulbright congratulating this man on his award.

It is difficult to describe my emotions in reading the letter and holding that broad man’s hand. I am no Senator Fulbright.

But since I am chair of the Fulbright board, my signature does go on similar letters to the thousands of Fulbright students and scholars going to more than 150 countries this year.

The man could see I was deeply moved. He smiled and said four words that I have heard unceasingly in the year and a half I have been on the Fulbright board. He said, “Fulbright changed my life.”

World leaders, Nobel Prize winners, poets, climate scientists, journalists, public health specialists, astronomers, engineers, filmmakers, business leaders. They all say the same thing: “Fulbright changed my life.”

Hearing that so often fills me with deep admiration for the genius Senator Fulbright had in creating this program. But it also gives me pause. Whatever we do, we can’t screw this up. Our job is to preserve this extraordinary legacy of international exchange and to extend the opportunity to countless more people. Their lives will be changed and they will change the lives of others.

You can think of a map of the world as a vast network of all these connected lives. A wounded but hopeful world – not flat, but more tightly-woven, more interdependent, more shared.

When I hear those words “Fulbright changed my life” I think of four other simple powerful words that President Obama often speaks when he reaches out to people in this divided time, “We’re in this together.”

But being in this together, sharing the world, changing lives – how does it happen? What’s the magic? How do we preserve it? Can we do it better?

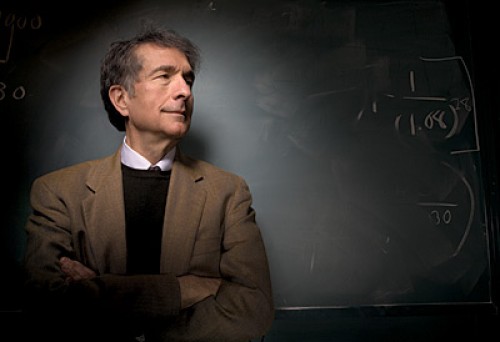

I was just reading about a Fulbright scholar from the Ukraine, Lyudmyla Baysara, who has been doing work on how we learn other languages – a critical part of the Fulbright experience. Dr. Baysara draws on the work of two great social scientists and – Howard Gardner and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Gardner created a well-known theory of multiple intelligences, which explains how people learn things in different ways, that there isn’t one way to measure people’s abilities.

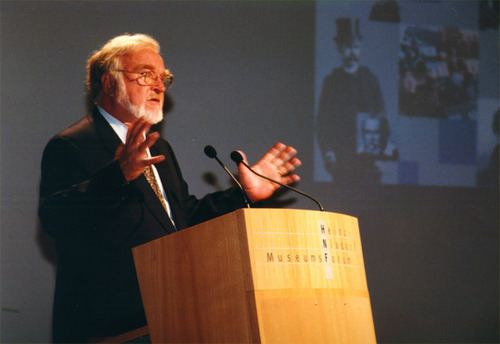

Csikszentmihalyi, a famous psychologist and himself a prominent Fulbright scholar, created the popular idea of “Flow,“ which is the sense of attention and engagement in work that makes people happy and productive by putting themselves in new experiences, creating a balance between new challenges and skills we already have – stretching ourselves to our limits.

We know the idea by many names: flow, being in the zone, in the groove – doing something that requires such intense concentration, everything else falls away.

And when that happens, Csikszentmihalyi says we experience a kind of ecstasy – literally standing outside ourselves – participating in a reality that is so different from everyday life.

In other words, exactly what is meant when people say, “Fulbright changed my life.”

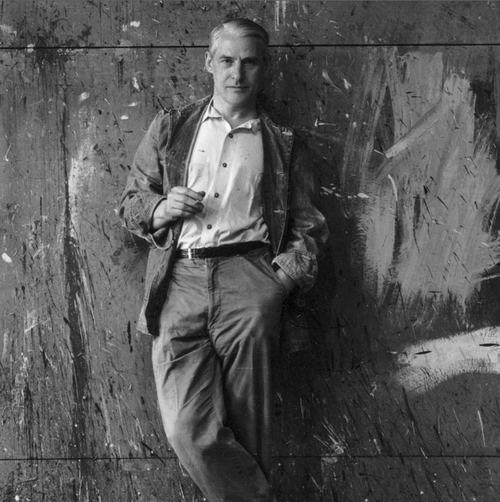

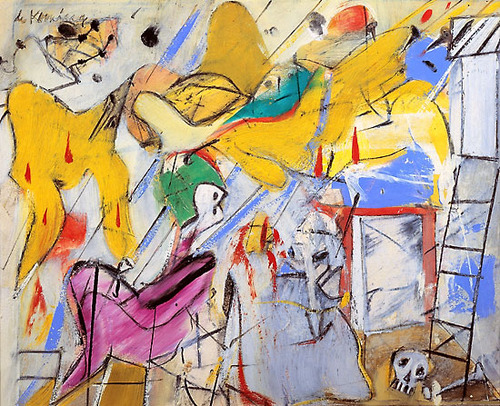

There is a story about the great modernist painter, Willem De Kooning:

A New York Times reporter was doing a piece on De Kooning and asked to observe him painting. De Kooning told him to occupy the building across the street and watch him from there. The reporter did. And he waited there for two days.

Nothing happened. De Kooning didn’t paint. He sat in a chair and listened to music.

The genius of Fulbright is that we don’t just wait for people to find that state. The whole idea of the exchange of people and ideas is that they are thrown outside their comforts – a new language, a new city or village, new friends and colleagues, different weather.

And then extraordinary things happen.

Csikszentmihalyi has made a very interesting observation about how this works: “If you are interested in something, you will focus on it.” Obvious enough. But, crucially, he adds, “and if you focus attention on anything, it is likely that you will become interested in it.”

“Many of the things we find interesting are not so by nature, but because we took the trouble of paying attention to them.”

At its core, Fulbright is all about taking the trouble of paying attention. Looking at the larger world, encountering people, experiences, values, and traditions different from our own.

Csikszentmihalyi took his notion of “Flow” and worked with Howard Gardner on his theory of multiple intelligences and wrote a book together called Good Work where they argue that, “if the fundamentals of good work – excellence and ethics – are in harmony, we lead personally fulfilling and socially rewarded lives.”

Fulbright is good work. It is good work done by extraordinary people. Yes, they are fulfilled and rewarded. But because of their linkages across the globe, because of what they do on their Fulbrights, they fulfill and reward others too. As Gardner said at a lecture I attended, “I want my children to understand the world, but not just because the world is fascinating and the human mind is curious. I want them to understand it so that they will be positioned to make it a better place.”

Could there be a better way of expressing the critical role of international education and programs like Fulbright?

Fulbright changes lives. And the world gets a little better.

It’s a privilege to play a small part in that mission. And I am so grateful to our partners such as IIE who play a profound role in the success of Fulbright. There is much to do. The world is out there. And it is not waiting.

Thank you.