Fulbright and the Giant Brain

from Essays

Remarks at the final gathering of NEXUS, the Fulbright’s pilot program for innovation and collaboration in science and technology in the Western Hemisphere.

Monday, April 23rd, 2012

Washington, D.C.

Good morning.

It’s a pleasure for me to be with this vanguard group of Fulbright scholars participating in our NEXUS experiment. And it’s an honor to join the directors of the Fulbright commissions throughout the Western Hemisphere whose imaginative thinking and leadership have made this new program a success. Welcome also to Fulbright’s many partners and the terrific team here at the State Department who have been provided wise and careful stewardship of NEXUS from the beginning.

I want to take you back in time this morning. To 1947.

Jackie Robinson signs with the Brooklyn Dodgers and becomes the first African-American player in professional baseball.

Marlon Brando stars on Broadway in A Streetcar Named Desire.

The first mobile phone is invented. The Polaroid instant camera.

The hologram. The transistor radio. Pilot Chuck Yeager breaks the sound barrier and Howard Hughes flies the Spruce Goose.

Alan Turing conducts the first experiments in artificial intelligence.

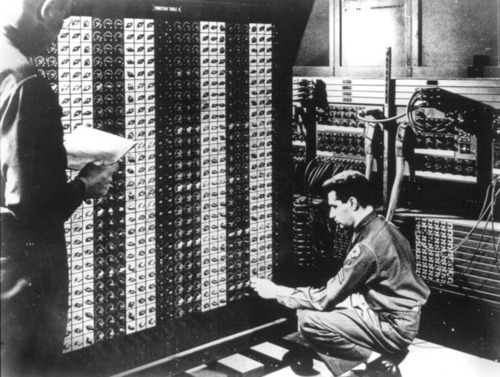

And the lights in the city of Philadelphia literally dim as the first digital computer is switched on. It is 100 ft long and weighs 30 tons. It has 18,000 vacuum tubes. The press calls it the Giant Brain. But its official name is ENIAC, the Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer.

ENIAC. That sounds like an acronym that could have been dreamed up here at the State Department.

Now something else happened in 1947 that millions of people have talked about ever since, and many say explained all this rapid advance in technology.

On July 8th, an alien spacecraft supposedly crash-landed in Roswell, NM.

Talk about foreign policy. That’s intergalactic engagement.

And there’s more. In 1947 the Marshall Plan was released. The UN voted on the partition that created the State of Israel. India and Pakistan were divided. The Voice of America began broadcasting behind the Iron Curtain.

Harry Truman gave the first televised presidential address.

And though the legislation was signed the year before, the first Fulbright scholars were named in 1947.

If scholarship programs were people, Fulbright would be getting its AARP card. Its senior citizenship papers. But as you twenty scholars participating in NEXUS know, Fulbright is just getting started.

Fulbright, as we’re going to hear over the next few days, is full of experiment and change. It’s feeling young and fit and trim and on the move.

Just like our Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, who—you’ve probably guessed it by now—was born in 1947.

There’s a reason I want to take you back to the first year of Fulbright, to its promise for creating mutual understanding in a fraught, complicated world.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the globe was in a state of rapid change and redefinition. There was science and there was science fiction. There was violence and there was diplomacy. There was fantasy and experiment.

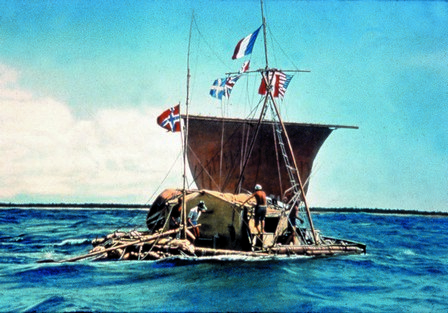

In 1947, the Norwegian explorer and writer Thor Heyerdahl pushed off from the coast of Peru and floated across the Pacific for 101 days in his raft Kon Tiki—hoping to show that Polynesia could have been settled by inhabitants of South America.

Most scientists now think Heyerdahl’s theory was wrong.

But let me read you another theory that appeared in American newspapers for the first time in 1947. It’s headline read: “WORLD IS WARMING UP, SAYS PROFESSOR.”

KEW .YORK (A.P.).-Professor Hans Ahlmann of the University of Stockholm, a prominent geographer and glaciologist now on a lecture tour of the United States, says the world is getting warmer. All over the world, even in the tropics, the temperature is rising, he says, adding that the Arctic glaciers are melting so fast that if something does not happen to retard the rate vast areas of in-habited coasts and low-lying country then various sections of the world may become flooded.

The more things change—well, they DON’T stay the same, do they?

The people in this room know the urgency.

You look at climate change and see that it demands solutions. You look at sustainability issues in a world of seven billion people and growing and you see the need for new energy sources and housing and food and health care and education and rewarding work.

At Fulbright, we talk frequently about innovation. It’s interesting that if you look at the history of that word, it doesn’t mean just making new discoveries. The Latin roots of innovation are two words—novus, which is new—coupled with in, which means new within the old.

Innovation is about the old being altered, getting renewed. It’s a subtle but powerful idea. The past isn’t discarded, it’s built upon. Innovation is rooted in the practical, it is grounded in the here and now – taking what we have and changing it, making it better, more useful, adapted to new needs.

Like the projects that you’ll discuss the next few days— turbines that usually need high winds being adapted to create ones that can work with micro winds, existing transportation networks that are changed to work more efficiently, present health care models that are being improved upon for immediate results.

That sense of the practical is what NEXUS is all about. And it makes me happy that nexus is not an acronym, but it’s also a powerful Latin word with practical meaning. Nexus is the active process of binding or joining together.

Here we are at a nexus of innovation in the Western Hemisphere. People from many disciplines, many nations collaborating. You began in Buenos Aires. You met again in Mexico. And now we are here in Washington, just one step in an ongoing process, one moment between 1947 and the future.

We on the Fulbright board have been with you at each of your meetings. Our former board chair, Anita McBride was at your first meeting. Ambassador Guerra-Mondragon was with you in Mexico City. All of us are eager to hear your progress and your ideas about this program over the next few days.

For us, Fulbright cannot and will not stand still. The entire program must innovate to meet the vast changes in how we teach and learn and share knowledge in the 21st century.

From the Arab spring to the explosive growth in Asia, from the crises in Europe to the rapid development of our own hemisphere, this program is global in ways that its founder could barely have imagined when that first group of Fulbright scholars arrived in 1947.

Some by ocean liner, some by train, perhaps a few on their flying saucer. Even with Fulbright scholars, there are some things we may never know.