Because a Fire Was In My Head

from Essays

from Lowell Boyer’s monograph, Emerge, 2009

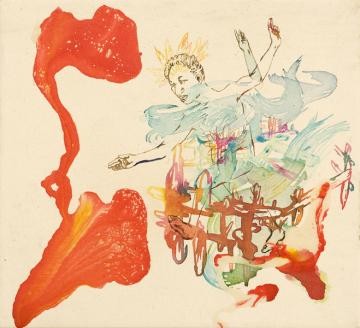

Lowell Boyers paints big. But not Julian Schnabel’s mountaintop grandiosity. Not Kiefer’s architecture of lead and straw and the burden of history. Not the controlled, pseudo-chaos of so much late, late abstraction. What’s large is the color and the gesture, the atmosphere and motion, the movement of brush and paint into figuration and events that the canvases can barely contain.

Boyers’ paintings radiate outward. It’s as if we’re witnessing the moments following internal combustions, as if Boyers has just broken a barrier between us and some inner world.

The surfaces are so liquid that color stains that world, saturates it with brilliance, but never seems to fix it into a rigid image. There is no ground, no sky, no horizon in these paintings. We look through cloud color, breath, vapor toward the glow of some inner space.

And what do we look in on? Who are the figures we see? I sometimes wonder whether Boyers has painted the atmospherics of people in the throes of Stendhal’s syndrome – the mysterious swoon, tears and rapturous fatigue that can come from experiencing something beautiful. It’s a lovely irony: to be looking at something beautiful that reveals what can happen when we look at something beautiful. It’s both a cautionary tale and an invitation.

Mark Rothko announced near the end of his life that it was his exuberantly colorful works, not the dark ones, that could be described as “tragic.” Perhaps he meant that color bleeds. We live in color, its joy and sharp pain. We can put darkness at a slight distance. But perhaps he meant that it’s our need to categorize, to live in assumptions, that is tragic – our need for an idea or statement or convenient label to possess, rather allowing art or the world to possess us.

There is always the danger in speaking and writing about art that we’ll fall prey to false categories, that we’ll assume that because we’ve put words around a painting, we’ve somehow understood it, that we’ll have stepped back and gained sufficient perspective.

Interestingly, Lowell Boyers’ paintings don’t tempt the grand explanation so much as they pull us inward. They crack a door open. It’s almost impossible not to want the impossible: to enter the canvas, to follow the frenzy within. After all, the paintings do provide us with all kinds of ladders and bridges.

But where do they lead?

Disturbing a river with man-made spans used to require the care of special priests. Romans called the bridge-builder a “pontifex” and his function was always as much to bridge the distance between the gods and man as it was to move people and horses across the Tiber. Bridges brought two realms into communication – with the risk of conquer and the possibility of love.

Every step we take on Earth

Takes us to a new world.

Every footstep lands

on a floating bridge.I know there is no straight road

In this world.

Only a vast labyrinth

Of intricate crossroads.

—Federico Garcia Lorca, “Floating Bridges”

That sense of being led somewhere by Boyers makes me think of figureheads on the prows of ships, an ancient tradition begun by the Chinese and Egyptians who painted eyes on their vessels to help them find their way. Boyers’s figures are often in profile, often looking to the left. Go west! (Is there no East?) And yet … Boyers’ figures often have their eyes closed or they’re squinting or blindfolded. Are they lost? In prayer? In pain? In reverie?

Whatever they’re doing, absorbed and theatrical, they are certainly not looking at us. And in our narcissistic time, the only thing more confusing – and compelling – than being looked at is not being looked at.

Notice too that the figures in Boyers’ paintings are never simply standing: they are kneeling, crouching, getting up, rolling forward, seeming to float or fall or fly. Ineluctable motion, but never moving: Wherever you go, there you are.

My possession of spiritual language is paltry. I step up the rung of Boyers’ ladders, out onto his bridges, with an unsure foot. I have to cling to the words of poets and philosophers who’ve journeyed inward far more deeply.

“If the place I want to get to could only be reached by way of a ladder, I would give up trying to get there. For the place I really have to get to is a place I must already be at now.” —Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Culture and Value”

But even without the vocabulary and the habits of faith, I am attracted to the mysticism – is there really another word? – expressed in these paintings. I feel a certain heartbreak of unknowing, but still have the hunch I might just know something, about the places these paintings reveal.

And I, infinitesimal being,

Drunk with the great starry

Void,

Likeness, image of

Mystery,

Felt myself but a part

Of the abyss,

I wheeled with the stars,

My heart broke loose on

The wind.

—Pablo Neruda, “Poetry”

“Broke loose.” That is not a condition we feel comfortable admitting in our world of attachments and arguments, in our quest for certainty and things. It is the condition of ecstasy, literally “standing outside or beyond” ourselves, that Boyers’ paintings portray and evoke and perhaps even provoke.

All good art states some claim to us and makes claims on us. As Arthur Danto has written, “Art presents a proposition in a sensuous medium, a way of expressing a truth.” And yet, in referring to the emotive power of Lowell Boyers’ paintings – their unsettling register neither in pure abstraction nor in the now-popular documentation, parody and critical engagement of our physical and political surroundings – I hope I am not seeming to imply that there is something morally didactic, exclusionary or narrow at work here. The paintings are not devotional; they aren’t signs of any cross or path. They are too strange, painterly and aesthetically-alive to be limited by spiritual impulse, however powerful that generative spirit might be.

Visionary language, visionary painting – these require a sincerity, an experience of being possessed, that we are so suspicious of in our cool, ironic, secular world. What’s particularly brilliant about Boyers’ work is that it is innocent in Blake’s sense of the word: his work is open and immediate, generous and aware, modest in its claims but ambitious in its painterly attention. Boyers somehow has the ability to displace all the signs of his effort with the feeling of his amazement. This is painting – let me reach to another great poet for help – that dwells in possibility.

When he is asked who the characters in his paintings are, Boyers often says they are “Everyman.” The word came into currency in the late 15th-century as the title of an English morality play, in which the eponymous protagonist is summoned to account by God for his wasted life. Everyman tries to bribe Death into sending someone else; when he’s refused, he seeks out a companion to make him less afraid. He pleads with Fellowship, Kindred and Cousin, Beauty, Strength, Possessions, and Wit – but all abandon him. Only Good Deeds will go with him beyond the grave.

In his long tradition in everything from epic poems to novels, songs, movies and videogames, Everyman is always constructed so the audience can imagine itself negotiating the same situations he encounters, without possessing special knowledge, skills or abilities. Everyman is not a hero. He gets hurt. He is a child of the plot and not his personality. Everyman’s most important feature is a highly polished surface, in which we can always see our own faint reflections.

It’s strange that, yes, we can see ourselves in Lowell Boyers’ paintings – because we so surprised, confused and entranced by what we see that we call ourselves into question. We wonder who we are.