A Requiem for Some Rogues

from Essays

Closing Keynote Address

The Louise Blouin Creative Leadership Summit

September 25th, 2013

New York City

In Memory of Kofi Awoonor

A few months after the revolution in Egypt, I met a young American artist named Erik Blome at the Academy of the Arts in Cairo.

I could tell Erik was a bit of a showman and he promised me an event if I were willing to stick around for the morning. We had tea. Then I was introduced to a dozen or so students and faculty. Lots of hugs for Erik as well as gossip and the cadging of cigarettes. Then Erik gathered everyone into a small courtyard for the first pouring of bronze that anyone could remember happening at an art school in Cairo.

Supplies at colleges are always limited in Egypt and there was no money for metal work. It seemed everyone was learning to repair sun-damaged antiquities. But Erik thought it was essential for these young artists to learn how to make and use bronze and he found the alchemy of it - melting, pouring, molding, pounding, polishing - too thrilling to pass up. He said there were great sculptors in that shaded dirt courtyard who just hadn’t been discovered yet. Everyone certainly looked as if they believed him. Erik was that kind of teacher.

His students had salvaged the necessary tin and copper from all over Cairo. And out of his own small living allowance, Erik paid for the kiln, propane, torches, safety goggles and much more. I kicked in all the cash I had in my pockets that day.

A crowd of fifty gathered around. Erik taught in English and broken Arabic, but mostly he taught with the movement of his body. His gestures of safety and calm, his encouragement to his hesitant assistants, his attention to shy students and to young women who’d been pushed to the back, bringing them forward–it was an one of those memorable experiences of seeing a master teacher. Time slowed. Two dull metals were transformed into a third, gleaming. It was just a small rectangular mold cooling in a hole in the dirt, but we looked at it as if we’d just dug up treasure from an undiscovered pharoah’s tomb.

Of course, even in your own backyard garden, there is always something solemn about digging into the earth. The slow rhythm of the shovel as it stabs into the dirt, the smell of soil and sweat, the awkward bend of your back, your body as machine, the mound that slowly balances the emptiness taking shape under your feet. You are connected to ancient rituals of planting, building or burying.

I think about that Saturday morning often. I’ve thought about it all this week, because as the world knows, this past Saturday morning, Kofi Awoonor, the great Ghanian poet, was shot dead having breakfast with his son in Nairobi, at the Westgate Mall.

Awoonor’s first name, Kofi, is the birth name given by the Ewe people of Togo and Ghana in West Africa to boys born on a Friday. It is not a name for death. It is not a name for the headlines on Saturday.

Awoonor was in Kenya taking part in the fifth Storymoja Hay literary festival. I have been to the Westgate Mall. I have been to the Nairobi Museum and its garden full of songbirds where Storymoja’s tents and banners and stages were set up on Saturday. And I met Awoonor once at another writer’s festival.

He was a traveler, a poet and scholar, a political prisoner turned diplomat, an ambassador to the United Nations, and, as he liked to say perhaps most devishly about himself, a rogue.

Interesting the history of that word: rogue came about in the 16th century on the edges of academic life. It’s from the Latin word that means to ask. Rogue was thieve’s slang for a vagabond beggar, someone who pretended to be a scholar in order to get some sympathy when he begged for food.

Not a strategy I would particularly recommend for the 21st century on the subway or outside the gates of Columbia or NYU. Nowadays, both scholar and rogue ask and shalt often not receive.

Awoonor called himself a rogue because despite his serious scholarly achievements and diplomatic credentials, he liked being the playfully mischievous outsider, larger than life, breaking convention, the solitary artist in love with his audience. “Not for nothing,” Awoonor wrote, “is the WORD an important part of magic.”

He also wrote once that the writer is someone who “pushes beyond the boundaries of the obvious …becomes more than a chronicler. He is a technician, magician, mythmaker, shaman, priest, diviner.” He fervently believed that all artists, all his fellow rogues, have responsibilities not only to themselves but to their communities. They must, he wrote, “keep faith with the artistic impulse of the community,” even as they found their own way.

It’s not an easy commandment to follow- a deep commitment to others as well as ourselves. It’s not even an understanding of what an artist is that many, at least in the West, continue to share. Irony, alienation, cynicism, doubt – truisms of our time that nonetheless don’t make it any easier for us to imagine or believe in “keeping faith” with anything.

But Awoonor was no easy optimist or cheerleader. He took his inspiration from the ancient stories of suffering of his Ewe ancestors. The Ewe are famous as poets and singers of the dirge, the lament for the dead, those expressions of loneliness and sorrow for those who have suffered and died, who have so rarely been able to go in peace The dirge tells the stories of what the Ewe believe is next in their journey. Since the recently dead are thought to be travellers between the living and the community of the past, The dirge is filled with messages and prayers of the living for the recently dead to carry to their ancestors, to the community of the past. By creating a link between the living and the dead, the dirge looks beyond present sadness.

Dirges are traditionally sung by Ewe women. Awoonor’s grandmother was an honored dirge singer. While the women sing, Ewe men carry drums on their heads and men who walk behind them play the drums. I don’t think you have any trouble that way feeling the rhythm deep in your bones.

The dirges themselves are songs of repetition. Exclamations and particular words are sung over and over as a way of making someone’s personal lament a chorus, a way for the community to enter the grief of the family – and the rhythm and repetition become ways of slowing down consciousness. Dwelling in the sounds of words and not their meanings helps ease the intensity of the grief by pulling mourners away from the intensity of the awful facts into a wave of shared feeling.

In the last 25 years of reliable electricity, now there are DJs at Ghanian funerals, what they call spinners. The mash-up of Brooklyn and Accra and all over from the West African diaspora of slaves, exiles and people seeking a better life is extraordinary to behold. Already, the dirges being sung for Awoonor have been profoundly beautiful in their sorrow.

We get the English word for dirge from the 8th verse of the 5th Psalm, which opens the Matins service in the Office of the Dead. “Dirige, Domine, deus meus“—"Direct, O Lord, my way in thy sight.” When we are lost, we need ways to direct us, people to help tell us what to do. Poetry can do that, songs can do that, tradition does that.

Who are we? How did we come to this? Every culture has its myths of origin and identity. The Ewe tell the story of their journey from Sumeria after the Biblical Floods, to Babel to Egypt long before Erik Blome, then through the Sudan to the hell of Ketume, which means “inside the grinding sand.”

The Ewe then fled the Sahara to Ethiopia, then west to the Niger, to Walata near Timbuktu, then down the coast, eventually into the snares of King Agokoli who ruled a kingdom called Notsie, in the south of present-day Togo. The tyrannical king made the Ewe people labor and hunt and fight for him. To enslave them, he made them build a huge wall around themselves –24 feet high and 18 feet thick–using whatever poor materials were at hand – thorns, brush, hedgehog bristles, broken pots, broken glass. By the end, their hands and feet were also broken, but not their spirit.

The Ewe storytellers say “Sise gli loo.” (Listen to the story.) And the people say, “Gli neva.” (Let the story come.)

Finally, the Ewe made a plan of escape. While the men did forced labor, the women marked one place on the giant wall where the entire community would splash all its wash water and waste to desecrate the wall with their anger and disgust, but also to weak its waddle and mud.

Eventually, a small part of the wall gave way and in the middle of the night a hole was made big enough for escape. But the Ewe didn’t just rush out. They turned around, and line after line, they hurried out backwards, so when the King came and saw the hole, at first he would be confused, seeing tracks in the mud coming in to the Kingdom. And while he tried to hunt down whoever supposedly snuck in, the Ewe who snuck out would have time to flee.

The Ewe celebrate this great escape every autumn on the first of November. They call the ceremony Hogbetsotso which means the day of uprooting and crossing over. It is a ceremony for remembering both suffering and joy. But this year, the joyful escape of the ancient Ewe will be remembered with the pain of honoring one of the Ewe’s great descendants, who did not escape, their son Kofi, born on Friday, killed on Saturday.

“Something has happened to me,” Awoonor wrote in “Songs of Sorrow,” one of his last works:

The things so great that I cannot weep …

I have wandered on the wilderness

The great wilderness men call life.

The rain has beaten me,

And the sharp stumps cut as keen as knives

I shall go beyond and rest.

I have no kin and no brother.

Death has made war upon our house.

So forgive me, that I’m here with this sadness, in this weather of pain and war and confusion, to close the Creative Leadership Summit with some thoughts on art and diplomacy.

I have my doubts.

One of the risks to getting art and diplomacy to work together is a tension inherent in the words themselves. The roots of the word “art” are words for skill, practice, preparing, and making. But diplomacy is founded on things already made.

Both diplomas and diplomatic papers are official documents that give license, authority and privilege. Diplomacy comes from the Greek word meaning “to double, fold over.” The privilege of a paper for your eyes only.

There’s certainly nothing new in associating art with privilege, with access and envy, with wealth and scarcity. I’m as thrilled as the next person to get an invitation to dinner, say, with the Ambassador to the Court of Saint James and have the opportunity to ogle the double Rothkos in Winfield House.

But if you’re asking art to matter – or even asking whether art does matter in making peace – then it seems essential that we should ask about the nature of that privilege, to keep asking hard questions about what art is, where it is, who sees it and how. Although, I wonder how tough we can be on ourselves with these questions at an exclusive lunch in a private, members-only club.

In fairness, the risk of art collected, supported and organized by governments and their embassies is essentially no different from the serious risk that exists to art in museums: the art might disappear.

And I mean this as a serious risk. It’s not only that art gets hidden and inaccessible behind the physical security fortresses of modern institutions, but that it can become invisible psychologically, collected among rarities and objects we’re meant to be impressed by, covetous of, art that’s a thing, not an experience.

Because the fact is, art as an experience is so damn fragile, so sensitive to our vices. If we’re not looking and even when we think we are, it can vanish before our eyes. Art might have status, it might have authority, but without our questions, without our flirtations and loitering, without our awkward openness, uncertainty, humility, the one thing art won’t have is us.

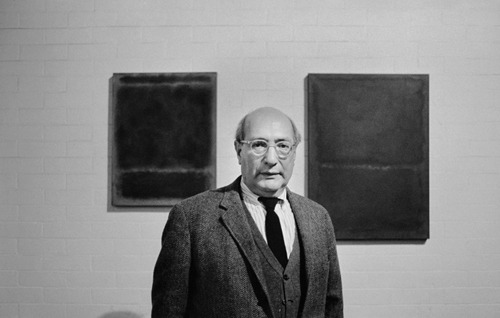

Let me turn to Marcus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz to help explain what I mean. Mark Rothko. Born today, September 25th, 1903.

We’ll all be having lunch after this talk, so we can consider it a birthday lunch for Rothko. He actually thought a lot about art and lunch. When he was commissioned to paint the famous murals for he Four Seasons Restaurant at the Seagram Buliding just a few blocks from here, he wrote to a friend, “I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room.”

Unfortunately, I’m told there are are no Rothkos in the dining room of the Metropolitan Club. But it gets back to the question of privilege and art, who sees it, where it needs to be. Rothko thought a lot about this. He wrote, “A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer.”

But–and the “but”, the qualification, the quarrel, is where Rothko always gets really interesting–though art lives by companionship, Rothko continued “It dies by the same token. It is therefore risky to send it out into the world. How often it must be impaired by the eyes of the unfeeling and the cruelty of the impotent.”

It’s risky to send art out into the world. You rarely hear that. Certainly, artists nowadays are not likely to be the romantics Rothko was. His spiritualism can seem foreign to us, in need, perhaps, of its own passport. But to me, there’s still such power in his anxieties, arrogance and doubt. And I hear in his reds, in the intensity of his colors, some sounds of lament and mourning and fear not unlike that rogue poet, Kofi Awoonor.

Because I knew I’d be in polite company this afternoon to talk about art and diplomacy on Rothko’s birthday, in a private club where men have to be gentle and wear a jacket and tie to get in the door, I thought I should clutter this elegant stage with the presence of yet another angst-ridden artist who would gladly have been rejected for membership, the great novelist Walker Percy.

In fact Percy wrote a novel aptly called The Last Gentlemen and it has a famous scene that conjures the fear I’ve been having about what happens when we try to do good with art, how risky it is that art really might disappear:

“Now here comes a citizen who has the good fortune to be able to enjoy a cultural facility. There is the painting … bought at great expense and exhibited in a museum so that millions can see it. What is wrong with that? Something, said the engineer, shivering and sweating behind a pillar.”

The protagonist, the engineer who is shivering and sweating is named Will and he’s bored and anxious because as Percy writes, the harder he looked at art in the museum, “The more invisible the paintings became.”

But then Percy brings a loud family into the museum. Will turns to look at them, as all of us would. And so does a museum worker who happens to be standing on a ladder touching up the ceiling in a corner of the gallery. The worker loses his balance and falls off the ladder. Will rushes over to help him up. And then, as Percy writes,

“It was at this moment that the engineer happened to look under his arm and catch sight of the Velázquez. It was glowing like a jewel! The painter might just have stepped out of his studio and the engineer, passing in the street, had stopped to look through the open door. The painting could be seen.”

Like Rothko, like the Ewe dirge singers, like Kierkegaard, whose birthday is not today, and countless other Cassandras of our passive consumer culture, Percy believed it is a constant struggle in contemporary life to stay awake, even to realize that we’re often sleepwalking, and then to find ways to recover ourselves, to experience things on our own, not just as we’ve been taught or told or assume they should be.

Percy was saying we should forget our superstitions about ladders. We should in fact go looking for them, because perhaps sometimes someone needs to fall off a ladder for us to see, though sometimes, of course, the trouble comes looking for us.

Official art, like official diplomacy, does not like rickety ladders in the gallery or on the stage, in view of the television cameras, messing with the scripted ceremonies. When they are hand in hand, art and diplomacy often seem to work hard to block out the trouble. But that may be exactly where the art is. If making things safe and comfortable and good, requires working hard to block out trouble, we ironically risk leaving art out in the cold.

50 years ago, in 1963, the art in embassies program was founded. Today is not my birthday either, but the program is almost as old as I am. JFK came to Manhattan for the ceremony at the Museum of Modern Art. Diplomacy was glamorous, the world was new.

And today, because of the generosity of donors and the creativity of artists, there are 10,000 art works exhibited in over 200 American missions around the world. But these are missions where increasingly you must be on the list, keep your ID out and visible, remove your shoes, empty your pockets and put everything onto the conveyer to be scanned before you’re let in.

I am not being facetious. These are the realities of a dangerous world. I have been to countless of these buildings in countries where the lives of diplomats are constantly in danger. I have known too many who have lost their lives. And I’d say without hesitation it’s better to have art inside these fortressed official buildings than blank walls or bland motivation posters with waving fields of grain. Who knows what art might do for the people who work there and others who do get in to see it.

But, again, the challenge I’m worrying about is inherent to the enterprise.

1963 was a big year for art and diplomacy. It was JFK and Jackie and art in embassies. And even better, it was the Mona Lisa. Step aside, Mr. Smith, because in 1963, Mona Lisa goes to Washington.

Perhaps even a Ewe dirge would have trouble capturing the extent of the Mona Lisa’s travels and travails. But there she was in Washington, 50 years ago, which, as it happens, was exactly 50 years after she famously came out of hiding. 50 plus 50: 100 years ago this fall, in 1913, the Mona Lisa showed up after going missing from the Louvre for almost two years.

I’m sure you’ve heard the famous story of how the Mona Lisa disappeared, how the painting was stolen and how no one at the Louvre even seemed to notice for more than a full day.

In fact, the Mona Lisa only seemed to become really visible at the Louvre after she left. When the theft hit the newspapers, people flocked to the Louvre. They lined up patiently just to stare silently at the empty space on the wall, where the painting had hung. More than one visitor left flowers.

Now close to 8 million people a year go to the Louvre to see her. Almost 90% of the museum’s visitors go just for that. It’s as if the entire population of New York got on the subway and got out at Pyramides Metro stop just to spend an average of 15 seconds in front of that lonely smile behind the bulletproof glass.

A few do more than that, of course. In 1956, a Bolivian man threw a rock at the painting and chipped Mona’s left elbow. In 1974, a Japanese woman sprayed it with red paint and just four years ago, a Russian woman who had been denied French citizenship threw a terra cotta mug at the painting. Talk about art and diplomacy. The woman bought the mug in the Louvre’s souvenir shop.

And then, of course, there are the Italians. Vincenzo Peruggia first stole the painting because he just wanted to take her home to the mother country after she was stolen by Napoleon. And recently Silvano Vincenti, the head of Italy’s National Committee for Culture and Heritage, got people looking at the painting very closely again because he seemed to be proposing a very contemporary kind of theft: identity theft. The sitter’s identity for the Mona Lisa has been assigned by scholars to at least ten different people over the years, but Vincenti claimed she wasn’t even a woman. He called a press conference to say that the real Mona Lisa was Leonardo da Vinci’s young male lover in drag, Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Orena, or Little Devil, as Leonardo liked to call him.

Of course, whether famous or not, official or not, the thing we’re talking about is art made strange, art made new. And there is no question that much effort in official projects of art and diplomacy is undertaken to do just that –countless projects to bring us in contact with the unfamiliar, to take us away from our safe habits of seeing things, to become aware just what a grip our culture has on our behavior, our personalities, our biases and values–whether it’s an anime film festival in Ghana sponsored by the Japan Society or the U.S State Department helping bring craftsmen from all over the Muslim world to help build the new galleries for art from the Mideast and Central Asia, these project do good, they enrich us.

Sometimes, art is talked of as one of the tools of diplomacy’s soft power, a way I can change your perceptions of me, so you might do something I want without me forcing you to.

And I believe passionately we must always try alternatives to force. People and governments need to persuade, people need to be persuaded. There is never a day without crisis, never an hour without the need for alternatives to violence. All hands on deck, all tools in hand. That great persuader with the cigar had an inimitable way of putting it. “Diplomacy,” Churchill said, “is the art of telling people to go to hell in such a way that they ask for directions.”

But that kind of “art” isn’t what art itself ever is. Art that persuades is art that disappears. Now maybe it’s good enough art that it can also be coopted and come to mean things officialdom didn’t intend. Maybe a man on a ladder comes crashing down.

When art is mis-recognized, its official purposes disavowed or some distance inevitably develops between what an institution wants and what an audience takes, then Awoonor’s magic happens. When art doesn’t have an agenda, it becomes a gift, a gift someone can take without any loss of self. Then, wonderfully, what you take, you can also give.

It’s what artists mean when they talk about inspiration, the breath they in-spire comes from the work of other artists. And breathing in, they’re given the energy, the urgency to make their own work, which then can become inspiration for others.

This, of course, is the famous “gift economy” that the anthropologist Lewis Hyde and many others have studied and written about with great eloquence. If art is an object, then if you have it, I don’t – like those gorgeous double Rothko’s inside the American ambassador’s home in London. Art then, is power, and even Churchill probably couldn’t have persuaded you to give it to me. And he didn’t have much use for abstraction.

But if art is an experience, a gift of time and memory, pain and love, then art can be inspiration, a gift you might take it and keep moving. And as it moves, through each of us, we make it grow. Since the armies keep growing and the resentments and scarcity and misunderstandings, we need the good things that come with peace to keep up and sometimes, if we’re lucky – as Kofi Awoonor was not – we might outpace the violence and hate.

Two final recommendations: try not to demand a jacket and tie or a name at the door or other rules and codes, diplomatic papers or privileges for entry. And try when you can to sneak a ladder on stage, with a bucket of paint precariously on top. If things get boring, you might just have to give it a little kick.